SEMINAR PAPER

TRANSHUMANISM AND ONE HEALTH

A CLOSER COOPERATION

This seminar paper is prepared for the Swiss THP, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. It is one of the outcomes of the Transhumanismus Kolloquium, Spring 2023, University of Basel, by Prof. Dr. Reinhold Bernhardt, Prof. Dr. Jakob Zinsstag, Dr. Andrea Kaiser-Grolimund.

University of Basel, Urban Studies, MA Critical Urbanisms

MA Critical Urbanism-University of Basel

MA Critical Urbanisms - Instagram

Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute

PREFACE

A LOOK AT THE INTERSECTION OF CITY AND HEALTH WITHIN THE SCOPE OF ONE HEALTH AND TRANSHUMANISM

City and health are concepts directly related to each other. Rapid and unplanned urbanization not only directly affects human health but also endangers the lives of not only humans but also animals and the entire ecosystem with the destruction it creates in nature. This is a subject that urban studies do not focus on much for some reason, but perhaps with COVID, we felt and experienced the vital bond between the city and health again. Cities are extremely suitable places for the spread of epidemics, and modern urban planning is responsible for this.

When examining cities and their development and trying to combine this with health, we must also take into account societies and their social, cultural, political, technological, and economic integrity and conditions. This is exactly where this study, prepared on behalf of One Health and Transhumanism, came to life. While One Health aims to bring integrity to the inevitable unity between humans, animals, and the environment in the name of health, transhumanism offers a broad perspective on the progress of humanity and focuses on the relationship between humans, non-humans, and the environment in the future. While we urban scientists establish all these future relationships, for some reason we ignore the issue of health. In fact, life can only progress as long as there is health.

While technology has many negative effects on health, it also has positive effects; we can also say this for cities. While the city contains unlimited opportunities for humans in many dimensions, it also creates a living space full of health hazards; all of these are topics worth examining in the name of urban studies. This also brings to the fore the distinction between rural areas and cities, and today we are perhaps worried that this distinction will disappear. The human population is increasing, already intense cities are getting bigger, and all this progress creates consequences that dominate nature and thus endanger human, animal, and environmental health.

We are transhumans; we have already gone beyond being simple humans with our superhuman skills, especially those adapted to urban life, and the tools, devices, and machines we use. What about our health? In all this development, most of us do not realize that our health is dedicated to urban life and that we sacrifice it for the sake of living in cities. This is the essence of the work being done on behalf of One Health and Transhumanism, and this issue should be a new focus for urban studies.

MODERN CITY AND HEALTH

Andrea Bagnato touches upon this issue in the context of modernity and health in his article titled Microscopic Colonialism (2017):

''For much of their history European cities have been unhealthy places. Until the end of the nineteenth century, they were traversed by waves of infection that would thrive in the close assemblage of people and livestock.

This may seem a distant past now that “health” is understood in opposition either to aging or to diseases, such as cancer, that are non- communicable. Yet, not only do infectious diseases remain a major cause of death outside Western countries, but scientists agree that the number of epidemic events around the world has actually been increasing. It is also widely accepted within biomedical science that there is a strong nexus between EIDs and the material footprint of capitalist processes of extraction and accumulation: mining, logging, and intensive agriculture have the effect of fragmenting wild habitats, increasing the risk of human exposure to pathogens in the wildlife.

In spite of such evidence, infectious diseases are conspicuously absent from the architectural discourse on urbanization. This arguably stems from a narrow understanding of the “urban,” which is still limited to the scale of the Western city. As Rem Koolhaas and others have argued, our focus on urban cores has made us blind to the human-driven changes that are taking place outside of them—whether in the countryside or in tropical rainforests.

Contrary to non-communicable diseases, epidemics are a direct function of urbanization: viruses, bacteria, and parasites can propagate only where enough people live close to one another. The size, density, and distribution of human settlements are thus crucial in determining how an epidemic spreads. This is why epidemics can only develop in settled societies—nomadic or seminomadic communities are generally too small and far apart for pathogens to spread effectively.

There is a close correspondence between the history of infectious diseases and the history of modern cities. In the nineteenth century, industrialization and globalization were paralleled by the onset of cholera and the intensification of tuberculosis. The fear of cholera in Europe and North America led to the reorganization of the city as a means of controlling individual health. Cholera epidemics continued, and it was only in the 1890s—with the discovery of bacteria and viruses—that public health became a matter of state intervention and centralized planning a political necessity. The provision of clean drinking water and subsidized housing were then recognized as universal goals, as were new medical protocols for immunization and disinfection. The concern with hygiene transformed urban planning long before it influenced architecture; only at the turn of the twentieth century did architects begin to internalize sanitary prescriptions. Modernism was founded on the promise of hygienic, urban, and social order.’’

MULTIDIMENSIONAL IMPACTS OF URBANISM ON ECOSYSTEMS AND HUMAN HEALTH

Agricultural practices

To understand the problematic relationship between health and city, we need to confront the conflict between modernism and traditionalism. Today, in many developing countries, especially in the global south, modernization of agricultural areas is not on the agenda for some reason during the modernization process of cities; failure to modernize agricultural practices reduces soil fertility and causes erosion. In this process, resisting modernization harms agricultural lands, water resources, and pasture lands that have strong ties to human, livestock, animal, and wildlife health. In order to reduce diseases, modern techniques must be harmoniously integrated into the interactions of humans, animals, nature, and cities.

Eco-violence

During the development of cities, people must avoid damaging biophysical environments (Unrus 1995). Today, in the global south, most nomadic pastoralists work, live, and reproduce in an environment challenged by deforestation, a decline in water resources, and unpredictable weather and climate variables. In addition, increasing population dynamics lead to infrastructure deficiencies caused by rapid urbanization; this should be one of the cases for urban studies. Pastoral production largely depends on the environment, which determines the content of the pastoral transhumance production process and animal welfare; the continuity of use of these areas for urbanization plays a decisive role in human and animal health.

Connectedness

Urban planners should resolve the disconnected systems paradox by adopting a whole-of-society approach that advocates that health should be represented in policies developed across all sectors of government and civil society. The temporal and spatial dynamics of any system depend on the properties of its constituent parts and the form of interactions between them, which is of vital importance for human and animal health in these societies in urban areas. Collective responsibility is vital in addressing social, environmental, and medical determinants in the provision of essential services such as water and sanitation, as well as vaccines that can be given to both animals and humans.

Planetary health

One health is supporting social justice, economic prosperity, and environmental protection in developing urban areas. In these societies where the interaction between humans and animals is intense, One Health can be expanded to include social and ecological consequences in parallel, taking into account the Sustainable Development Goals. Recognizing that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and ecosystems is closely linked and interdependent, One Health improves disease management by bringing together medical, veterinary, and environmental scientists for social and environmental sustainability; therefore, the concept of One Health should engage in urban studies.

ONE HEALTH TRANSHUMANISM

INTEGRATING THE ASPECTS OF ONE HEALTH INTO THE VISION OF TRANSHUMANISM IN RELATION TO THE MORE TECHNOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS

This paper prospectively aims to examine what relations could be established between aspects of One Health and the transhumanist movement in the technological context based on the scientific, social, and philosophical dimensions of this relationship. Should this analysis seem to expand the holistic health concept of the One Health concept, it actually aims to observe the change of humankind in the context of his interactions with all kinds of beings, whether human or not, living or non-living, within the dynamics of Transhumanism.

Transhumanism is one of the most important movements of recent years, with immense social, scientific, and philosophical orientations that have sparked heavy debate. However, by looking at it from various perspectives, it is easy to realize that we are all already transhumans and programmed to surpass ourselves with our posthuman characters with all the technology that has developed intensely. So, how will this development, the unpredictable progress of technology, affect humanity, non-humans, and ecology in the sense of global health? In the future, One Health and Transhumanism may have to share common denominators and be forced to reshape the concept of health.

ONE HEALTH

A HARMONIC DEVELOPMENT OF PLANETARY GLOBAL HEALTH

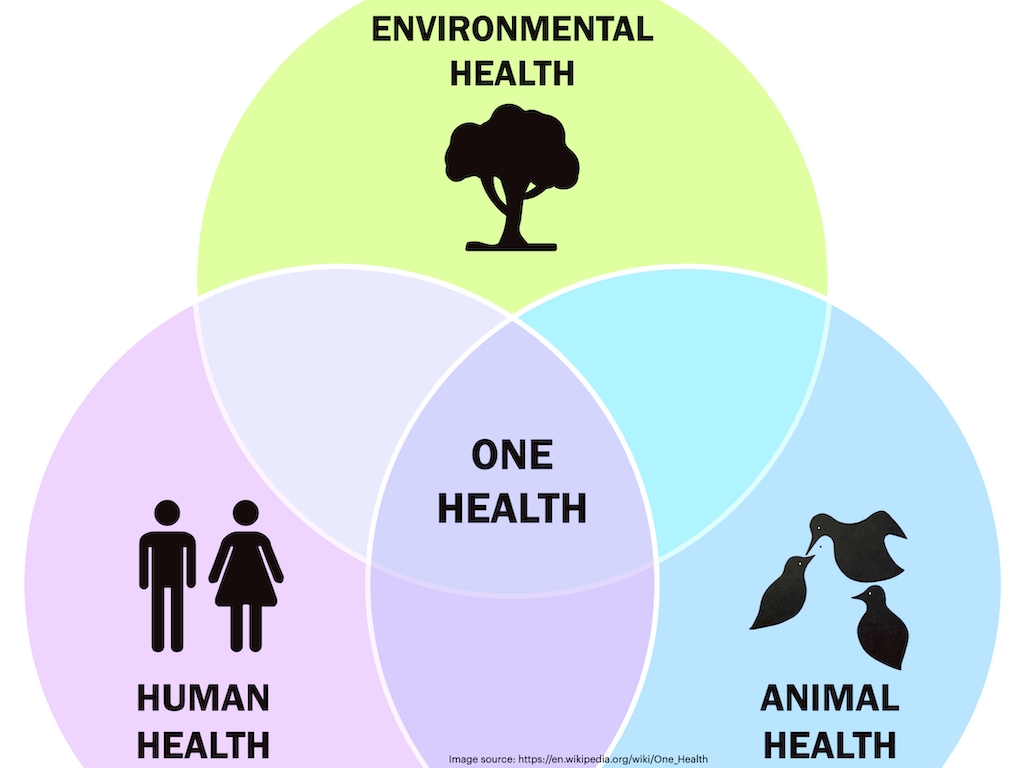

Humans and animals are inextricably linked to ecological systems, both natural and manmade, called cultural and social systems. One Health is an approach that recognizes that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment. It implies an interface of humans and animals with the environment, which can be highly complex, requiring systemic approaches to the physical and social environment.

One Health is a collaborative, multisectoral, and transdisciplinary approach, working at the local, regional, national, and global levels with the goal of achieving optimal health outcomes by recognizing the interconnection between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment. One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems.

One Health recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent. While health, food, water, energy, and the environment are all wider topics with sector- specific concerns, collaboration across sectors and disciplines contributes to protecting health, addressing health challenges such as the emergence of infectious diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and food safety, and promoting the health and integrity of our ecosystems.

ONE HEALTH

KEY FACTS

• The health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is closely interlinked. Changes in these relationships can increase the risk of new human and animal diseases developing and spreading.

• The close links between human, animal, and environmental health demand close collaboration, communication, and coordination between the relevant sectors.

• One Health is an approach to optimizing the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems by integrating these fields rather than keeping them separate.

• Some 60% of emerging infectious diseases that are reported globally come from animals, both wild and domestic. Over 30 new human pathogens have been detected in the last three decades, 75% of which originated in animals.

• Human activities and stressed ecosystems have created new opportunities for diseases to emerge and spread.

• These stressors include animal trade, agriculture, livestock farming, urbanization, extractive industries, climate change, habitat fragmentation, and encroachment into wild areas.

One Health is about interdisciplinary collaboration between different academic disciplines, primarily underpinning human and veterinary medicine but with strong links to the natural and social sciences and the humanities.

TRANSHUMANISM

THE ANTI-HUMAN CHARACTER OF TECHNOLOGICAL REVOLUTION

Transhumanism is a philosophical and scientific movement that advocates the use of current and emerging technologies such as genetic engineering, cryonics, artificial intelligence (AI), and nanotechnology to augment human capabilities and improve the human condition. Transhumanists envision a future in which the responsible application of such technologies enables humans to slow, reverse, or eliminate the aging process, achieve corresponding increases in human life spans, and enhance their cognitive and sensory capacities. The movement proposes that humans with augmented capabilities will evolve into an enhanced species that transcends humanity, the "posthuman."

"We advocate the well-being of all sentient beings, including humans, non-human animals, and any future artificial intellects, modified life forms, or other intelligences to which technological and scientific advance may give rise. We favor allowing individuals wide personal choice over how they live their lives.” Transhumanist Decleration

TRANSHUMANISM

HISTORY, ETHICS, AND PHILOSOPHY

The term Transhumanism was popularized by the English biologist and philosopher Julian Huxley in his 1957 essay of the same name. Huxley held that it was now possible for social institutions to supplant human evolution in refining and improving the human species. In the 1980s, newly formed transhumanist organizations and schools of thought advocated human life extension, cryonics, space colonization, and futurism. In 1986, the American engineer K. Eric Drexler published Engines of Creation, an exploration of the future applications of nanotechnology and molecular manufacturing. Also in the 1980s, the American conceptual artist Natasha Vita-More published an evolving manifesto of Transhumanism and the "Transhumanist Arts Statement," which announced the "designing" of a future that merged aesthetics with science and technology to enhance sensory experiences and to improve and extend human life. In the 1990s, "extropianism," a libertarian doctrine that advocates overcoming human limitations through technology, came to the forefront of the transhumanist movement. In 1998, the Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom and the British philosopher David Pearce founded WTA, the World Transhumanist Association that promoted Transhumanism as a serious academic discipline.

As transhumanist ideas developed from theory to actuality in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, ethical concerns increasingly played a central role in transhumanist philosophy. Scientific breakthroughs, including stem cell therapies, in vitro fertilization, brain chips, animal cloning, exoskeletons, artificial intelligence, and genomics, have redirected the dialogue between Transhumanism’s proponents and its critics from the future to the present.

TRANSHUMANISM

TOWARDS TRANSSPEICES IN TECHNOCRATIC SOCIETIES

The aims of the transhumanist movement are summed up by Mark O’Connell in his book To Be a Machine. "It is their belief that we can and should eradicate aging as a cause of death; that we can and should use technology to augment our bodies and our minds; that we can and should merge with machines, remaking ourselves, finally, in the image of our own higher ideals."

The idea of technologically enhancing our bodies is not new. But the extent to which transhumanists take the concept is In the past, we made devices such as wooden legs, hearing aids, spectacles, and false teeth. In the future, we might use implants to augment our senses so we can detect infrared or ultraviolet radiation directly or boost our cognitive processes by connecting ourselves to memory chips. Ultimately, by merging man and machine, science will produce humans who have vastly increased intelligence, strength, and lifespans, a near embodiment of gods.

Is that a desirable goal? Advocates of Transhumanism believe there are spectacular rewards to be reaped from going beyond the natural barriers and limitations that constitute an ordinary human being. But to do so would raise a host of ethical problems and dilemmas. As O’Connell’s book indicates that the ambitions of Transhumanism are now rising to the top of our intellectual agenda. But this is a debate that is only just beginning. “We are now approaching the time when, for some kinds of track sports such as the 100-meter sprint, athletes who run on carbon-fibre blades will be able to outperform those who run on natural legs.’’, says Blay Whitby, Sussex University.

TRANSHUMANISM

TECHNOLOGICAL MENTALITY & TECHNOLOGICAL FORMS OF LIFE

David Vintiner, a British photographer, has been following the transhumanist subculture for the past two years. He divides his pictures of transhumanists, some of which are reproduced here, into three groups: those who are working to extend life, those toying with implants as body art, and those attempting to make permanent changes to the human condition. The picture shown captures precisely the ironies that were on display in Austin, Texas: the odd union between scientific innovators and garden- shed fantasists.

''They shared knowledge of the newly understood plasticity of the brain and a utopian idea of technology and were pushing that understanding in novel, homemade directions. They were, at least, the most convincing hints that this introverted subculture, which styles itself as transhuman," was sometimes knocking at the doors of perception just as determinedly as those early experimenters with hallucinogenic drugs in the last century.’'

Speaking to the people in Vintiner’s pictures, you hear about some of those risks, but also the extent of new technological possibilities and the current limits to them. We have become used to implants to fix medical problems, such as diabetes and heart conditions. And as a culture, we have long accepted the therapeutic possibilities of plastic surgery. But the idea that we might augment our natural senses and abilities through surgery remains a difficult ethical question.

THE TECHNOLOGICAL UTERUS OF THE CYBERNETIC FUTURE HUMAN SPECIES

TRANSHUMANISM: THE ANTI-HUMAN ESSENCE WITH TECHNOLOGIZED HUMANKIND

INTEGRATING THE VISION OF “TECHNOLOGIZED HUMANS” INTO ONE HEALTH

From the transhumanist point of view, a broader discussion of how the technologization of humankind should proceed to global health could be a vertical integration of the topic into the aspects of One Health. Yet, the philosophical dimensions of this process could be part of the medical and biological sciences, and the basic understanding of human-machine-technology interactions could be part of philosophy. Then, technological history and futures could be part of the social sciences, and technological education could be part of the pedagogy. This transition beyond transdisciplinarity would bring a new understanding of Transhumanism from its ethical and moral courses to ontological and scientific dimensions, just like us, our bodies, and living systems that we want to keep working as machines.

We need to understand the concept of health in different ways, considering also non-humans, which would help One Health understand better the effect of Transhumanism on health. At this point, the close relationship between biology and technology can solve human health problems caused by accidents, which can improve human general health and well-being. Merging humans, machines, science, and technology can create a new opening in the field of health in the future, and the transhumanist movement can be a pioneer in this regard on behalf of One Health.

DEPERSONALIZATION OF MAN: THE DEFINITION OF HUMAN NO LONGER CONTAINS US

A TRANSHUMANIST SUBCULTURE EXISTS SOMEWHERE BETWEEN ART, MEDICINE, AND COUNTERCULTURE

WE THUS CALL THE FOUNDATIONAL QUESTIONS OF THE BOND BETWEEN ONE HEALTH AND TRANSHUMANISM

1. Could Transhumanism be part of One Health's future? How could they benefit from closer cooperation?

2. How would Transhumanism affect human health in the context of human-animal and human-environment interactions? How could it position human beings in all this interaction as the main working area of One Health?

3. How could One Health find a way to adapt Transhumanism to its content to develop its skills towards a more technological content? And would this be a desirable goal?

4. Aren't we already transhumans with all the machines, devices, and tools that surround us and serve to develop and improve our abilities, and aren't all medicines that provide with the concept of Transhumanism already part of One Health? How would One Health evaluate the humans in this content?

5. How would One Health address human-machine-technology interactions in the context of Transhumanism and their impact on human health and the lives shaped through their impact on the built and unbuilt environment? How would this affect ecohealth, a broader concept of an ''ecosystem approach to health’'?

MA Critical Urbanisms, University of Basel

Spring 2023

Accessor: Prof. Dr. Jakob Zinsstag

Issued by: Engin Tulay

SOURCES

Transhumanismus Kolloquium, Spring 2023, University of Basel, Prof. Dr. Reinhold Bernhardt, Prof. Dr. Jakob Zinsstag, Dr. Andrea Kaiser- Grolimund. Class Notes.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, One Health available from https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/index.html

One Health, Human and Animal Unit available from https://www.swisstph.ch/en/about/eph/human-and-animal-health

World Health Organization available from https://www.who.int/health-topics/one-health#tab=tab_1

When man meets metal: Rise of the transhumans available from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/oct/29/transhuman- bodyhacking-transspecies-cyborg

No death and an enhanced life: Is the future transhuman? available from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/may/06/no- death-and-an-enhanced-life-is-the-future-transhuman

What is transhumanism? available from https://www.humanityplus.org/transhumanism

The Transhumanist Declaration available from https://www.humanityplus.org/the-transhumanist-declaration

Transhumanism available from https://www.philosophytalk.org/blog/transhumanism

Transhumanism, social and philosophical movement available rom https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hans-Moravec

The anti-essence of transhmanism available from https://orthochristian.com/150294.html

The technological singularity and the transhumanist dream available from https://revistaidees.cat/en/the-technological-singularity-and- the-transhumanist-dream/

How transhumanism would like to manufacture the elite of the future available from https://up-magazine.info/en/le-vivant/homme- augmente/7647-le-transhumanisme-voudrait-fabriquer-l-elite-du-futur-2-2/

Transhumanismus – Die Vision der technologischen Evolution des Menschen. Die Vision der technologischen Evolution des Menschen available from https://hwzdigital.ch/transhumanismus-die-vision-der-technologischen-evolution-des-menschen/

Bagnato, A.(2017) Microscopic Colonialism available from https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/positions/153900/microscopic- colonialism/