COURSE

CRITICAL URBANISMS: INTRODUCTION

University of Basel, Urban Studies, MA Critical Urbanisms

18-22 September 2023

Kenny Cupers, Andrew Tucker, Lea Nienhoff

''The course introduces selected current debates in critical urban studies generally and to themes that frame the Masters in Critical Urbanisms in particular. In order to explain why urban problems persist or how cities change the way they do, observers often rely on unspoken assumptions, theoretical constructs, or inherited perspectives. Their explanations, in turn, are used by a range of actors to legitimize policies or mobilize forms of intervention.

The way a problem is defined shapes the approaches that actors mobilize in response. Critical approaches to urban studies therefore require us not only to account for the complexity of urban realities but also to interrogate the various ways in which people make sense of them.

Drawing from the disciplines of geography, architecture, law, political science, history, and anthropology, this course explores the relationship between urban challenges, urban theories, and urban practices. Students will learn to unpack and explicate ways of seeing and making sense of cities and landscapes and explore how research paradigms bear on specific theories as well as practices and lived experience. Our goal is to explore the “real-world” work of theory and the ways it can help reframe urban challenges and shape alternative modes of engagement.'' Kenny Cupers, Andrew Tucker, Lea Nienhoff

MA Critical Urbanism-University of Basel

MA Critical Urbanisms - Instagram

JOURNAL

Prepared for the Course Assessment

JOURNAL

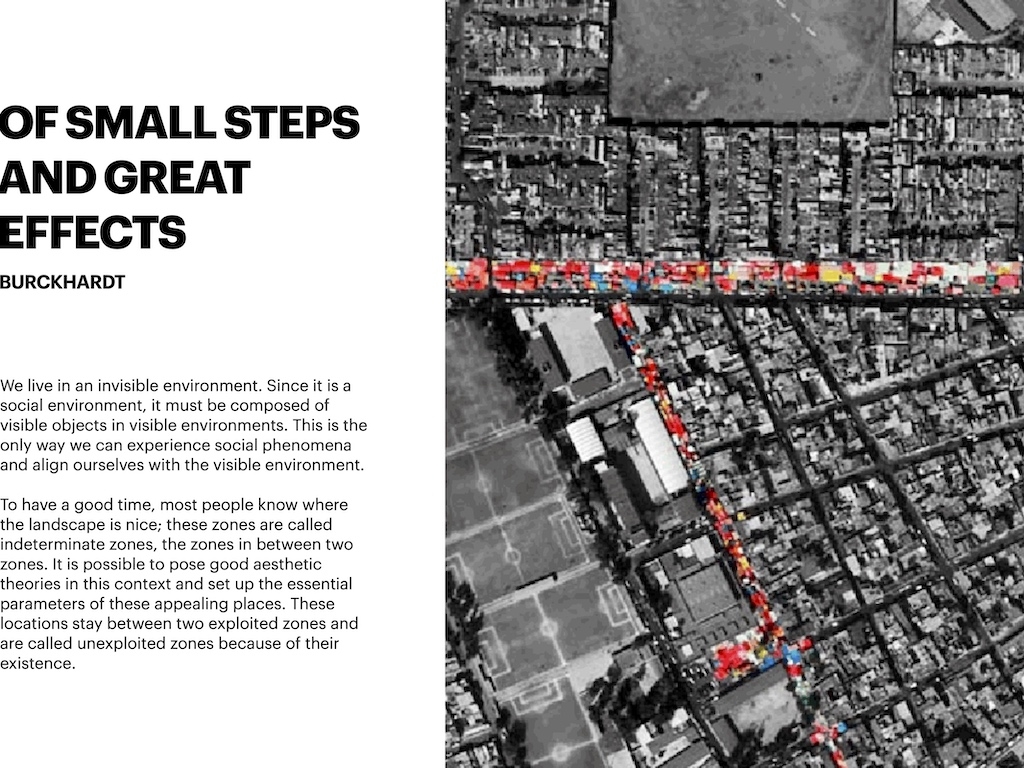

OF SMALL STEPS AND GREAT EFFECTS

BURCKHARDT

We live in an invisible environment. Since it is a social environment, it must be composed of visible objects in visible environments. This is the only way we can experience social phenomena and align ourselves with the visible environment.

To have a good time, most people know where the landscape is nice; these zones are called indeterminate zones, the zones in between two zones. It is possible to pose good aesthetic theories in this context and set up the essential parameters of these appealing places. These locations stay between two exploited zones and are called unexploited zones because of their existence.

CHILDREN'S BOOKS

BURCKHARDT

Children's books have such designed environments that are socially pure and physically lovely, where the social roles are stable. These books offer a world where the social roles are clear, but the zones are not; the zones in these books are extensive and socially ambiguous.

The environment we live in should be considered in a way where social roles are encouraged and anticipated in order to justify the social structures, postures, and phenomena. In addition, following the modern movement, there are evolved arguments that suggest a certain type of satisfaction in the living environment, where people should be content. Therefore, the environment should accordingly be designed in a way we can dream of feeling complete in our mind’s eye.

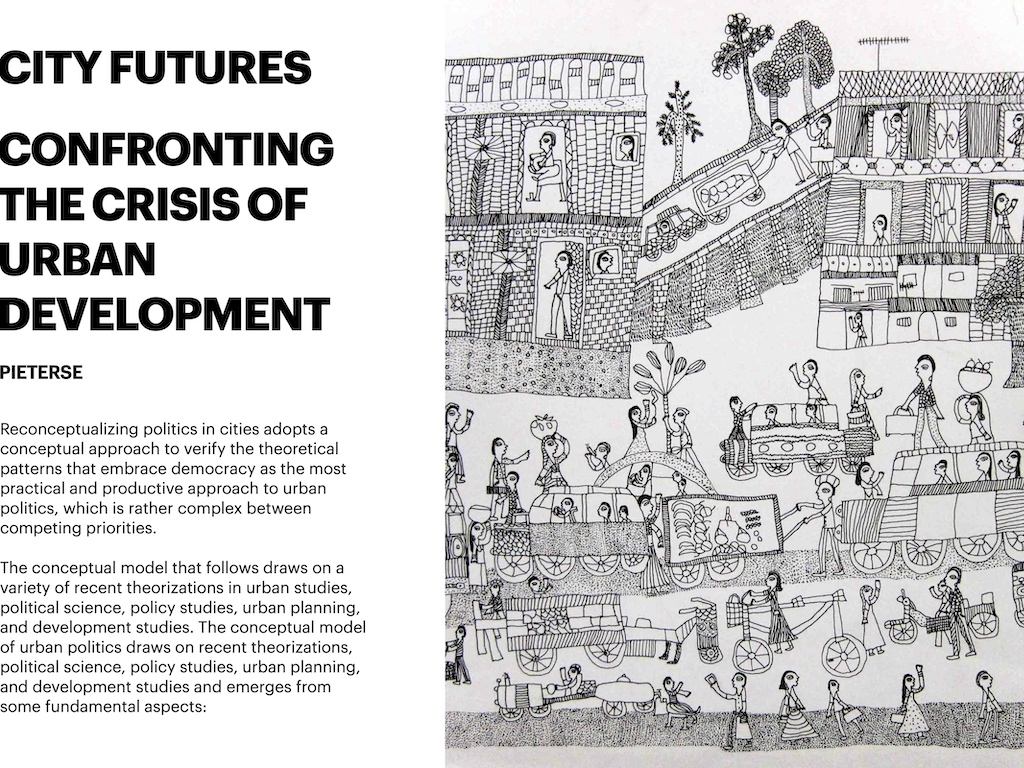

CITY FUTURES

CONFRONTING THE CRISIS OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT

PIETERSE

Reconceptualizing politics in cities adopts a conceptual approach to verify the theoretical patterns that embrace democracy as the most practical and productive approach to urban politics, which is rather complex between competing priorities.

The conceptual model that follows draws on a variety of recent theorizations in urban studies, political science, policy studies, urban planning, and development studies. The conceptual model of urban politics draws on recent theorizations, political science, policy studies, urban planning, and development studies and emerges from some fundamental aspects:

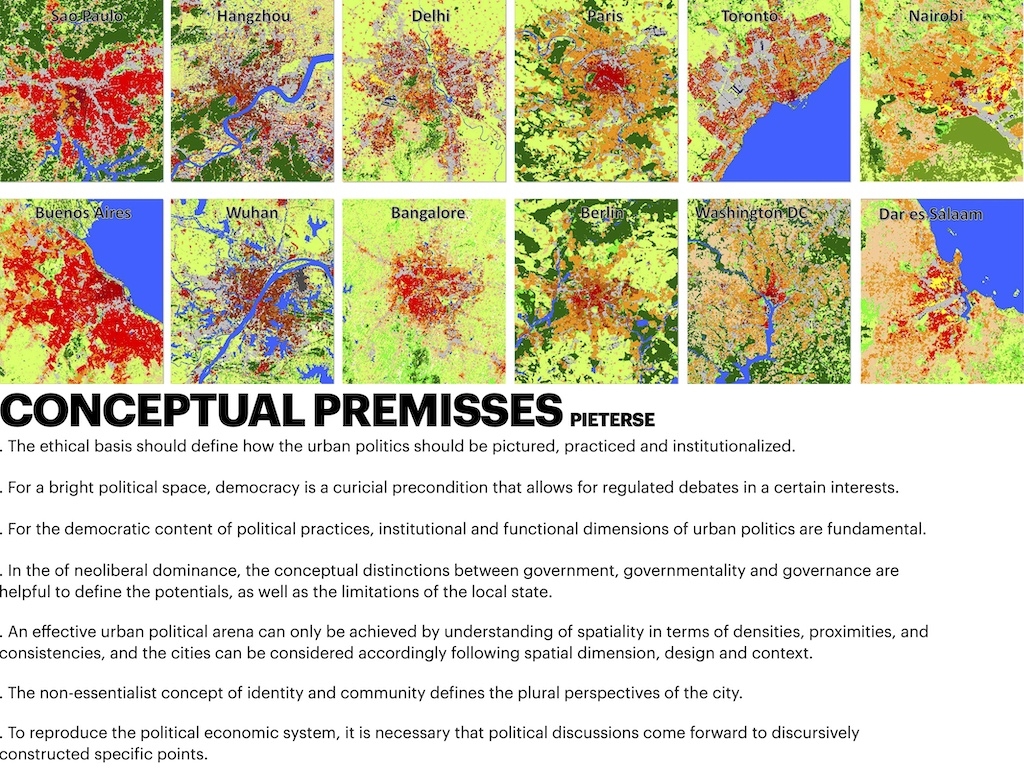

CONCEPTUAL PREMISSES

PIETERSE

. The ethical basis should define how the urban politics should be pictured, practiced and institutionalized.

. For a bright political space, democracy is a curicial precondition that allows for regulated debates in a certain interests.

. For the democratic content of political practices, institutional and functional dimensions of urban politics are fundamental.

. In the of neoliberal dominance, the conceptual distinctions between government, governmentality and governance are helpful to define the potentials, as well as the limitations of the local state.

. An effective urban political arena can only be achieved by understanding of spatiality in terms of densities, proximities, and consistencies, and the cities can be considered accordingly following spatial dimension, design and context.

. The non-essentialist concept of identity and community defines the plural perspectives of the city.

. To reproduce the political economic system, it is necessary that political discussions come forward to discursively constructed specific points.

PROLOGUE: LOSE YOUR MOTHER

HARTMAN

‘’Obruni; a stranger, a foreigner from across the sea. Obruni forced me to acknowledge that I didn’t belong anyplace. Secretly I wanted to belong somewhere or, at least, I wanted a convenient explanation of why I felt like a stranger.''

''My appearance confirmed it, I was the proverbial outsider. The domain of the stranger is always an elusive elsewhere. I was born in another country, where I also felt like an alien and which in part determined why I had come to Ghana.'

THE PATH OF STRANGERS

HARTMAN

''The most universal definition of the slave is a stranger. I had to come to Ghana in search of strangers. Slavery had established a measure of man and a ranking of life and worth that has yet to be undone. I chose Ghana because it possessed more dungeons, prisons, and slave pens than any other country in West Africa. Neither blood nor belonging accounted for my presence in Ghana, only the path of strangers impelled toward the sea.''

''Slavery was never mentioned at my school. Being a stranger concerns not only matters of familiarity, belonging, and exclusion but as well involves a particular relation to the past. I am the vestige of the deadened history is how the secular world attends to the dead.''

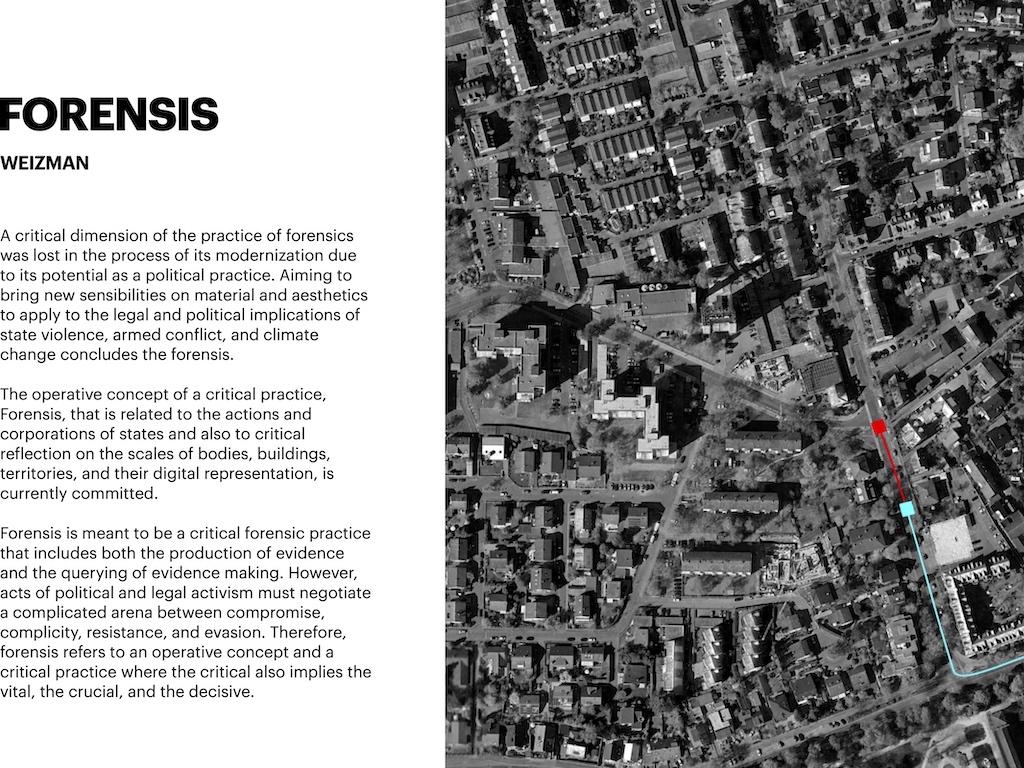

FORENSIS

WEIZMAN

A critical dimension of the practice of forensics was lost in the process of its modernization due to its potential as a political practice. Aiming to bring new sensibilities on material and aesthetics to apply to the legal and political implications of state violence, armed conflict, and climate change concludes the forensis.

The operative concept of a critical practice, Forensis, that is related to the actions and corporations of states and also to critical reflection on the scales of bodies, buildings, territories, and their digital representation, is currently committed.

Forensis is meant to be a critical forensic practice that includes both the production of evidence and the querying of evidence making. However, acts of political and legal activism must negotiate a complicated arena between compromise, complicity, resistance, and evasion. Therefore, forensis refers to an operative concept and a critical practice where the critical also implies the vital, the crucial, and the decisive.

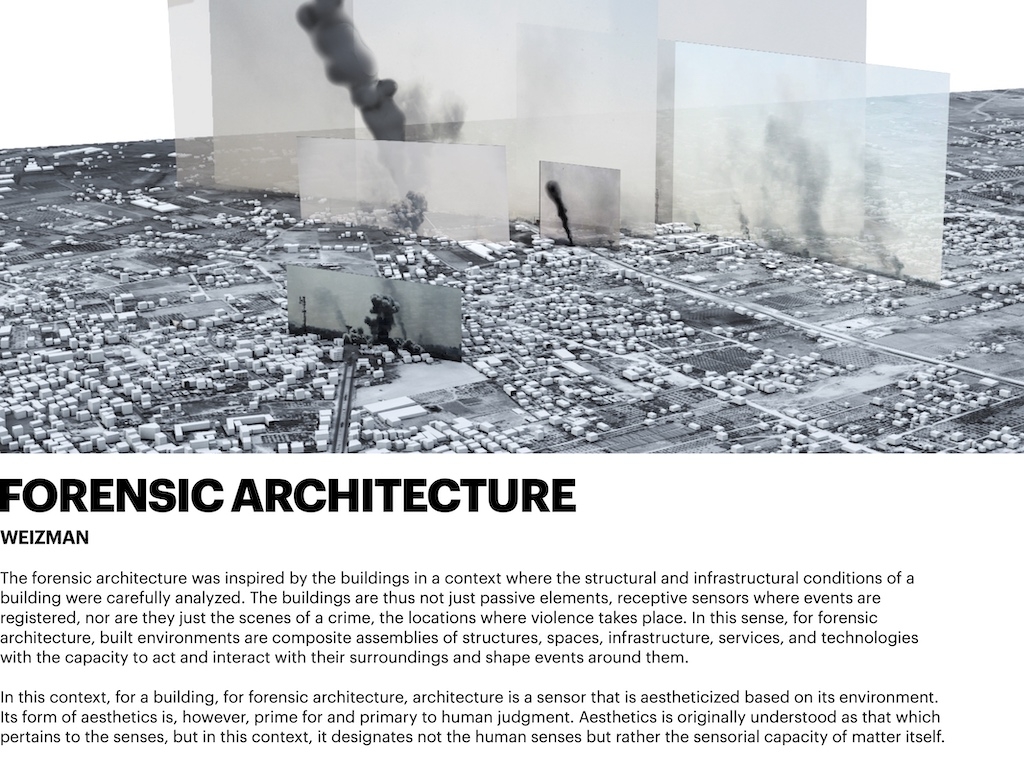

FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE

WEIZMAN

The forensic architecture was inspired by the buildings in a context where the structural and infrastructural conditions of a building were carefully analyzed. The buildings are thus not just passive elements, receptive sensors where events are registered, nor are they just the scenes of a crime, the locations where violence takes place. In this sense, for forensic architecture, built environments are composite assemblies of structures, spaces, infrastructure, services, and technologies with the capacity to act and interact with their surroundings and shape events around them.

In this context, for a building, for forensic architecture, architecture is a sensor that is aestheticized based on its environment. Its form of aesthetics is, however, prime for and primary to human judgment. Aesthetics is originally understood as that which pertains to the senses, but in this context, it designates not the human senses but rather the sensorial capacity of matter itself.

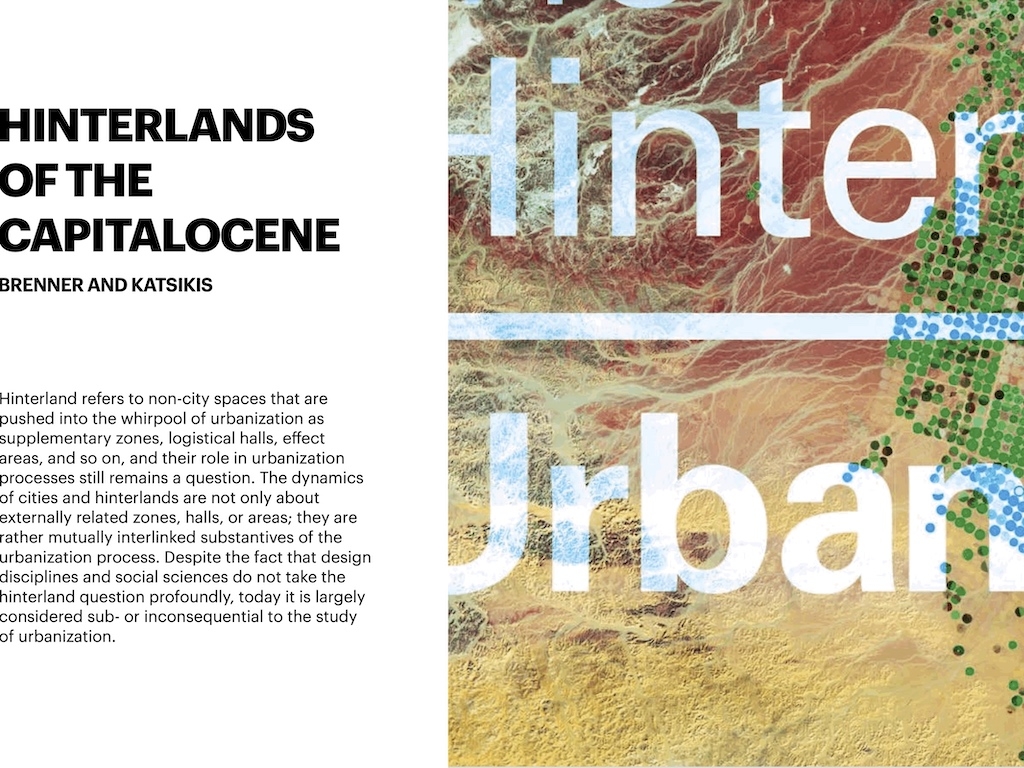

HINTERLANDS OF THE CAPITALOCENE

BRENNER AND KATSIKIS

Hinterland refers to non-city spaces that are pushed into the whirpool of urbanization as supplementary zones, logistical halls, effect areas, and so on, and their role in urbanization processes still remains a question. The dynamics of cities and hinterlands are not only about externally related zones, halls, or areas; they are rather mutually interlinked substantives of the urbanization process. Despite the fact that design disciplines and social sciences do not take the hinterland question profoundly, today it is largely considered sub- or inconsequential to the study of urbanization.

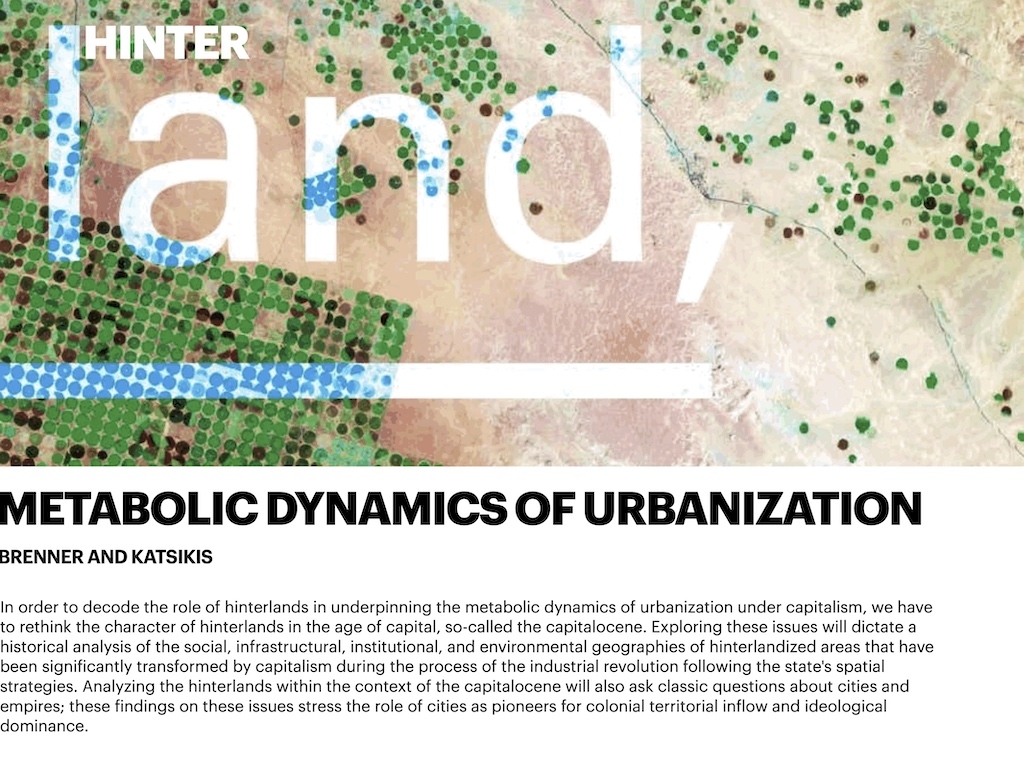

METABOLIC DYNAMICS OF URBANIZATION

BRENNER AND KATSIKIS

In order to decode the role of hinterlands in underpinning the metabolic dynamics of urbanization under capitalism, we have to rethink the character of hinterlands in the age of capital, so-called the capitalocene. Exploring these issues will dictate a historical analysis of the social, infrastructural, institutional, and environmental geographies of hinterlandized areas that have been significantly transformed by capitalism during the process of the industrial revolution following the state's spatial strategies. Analyzing the hinterlands within the context of the capitalocene will also ask classic questions about cities and empires; these findings on these issues stress the role of cities as pioneers for colonial territorial inflow and ideological dominance.

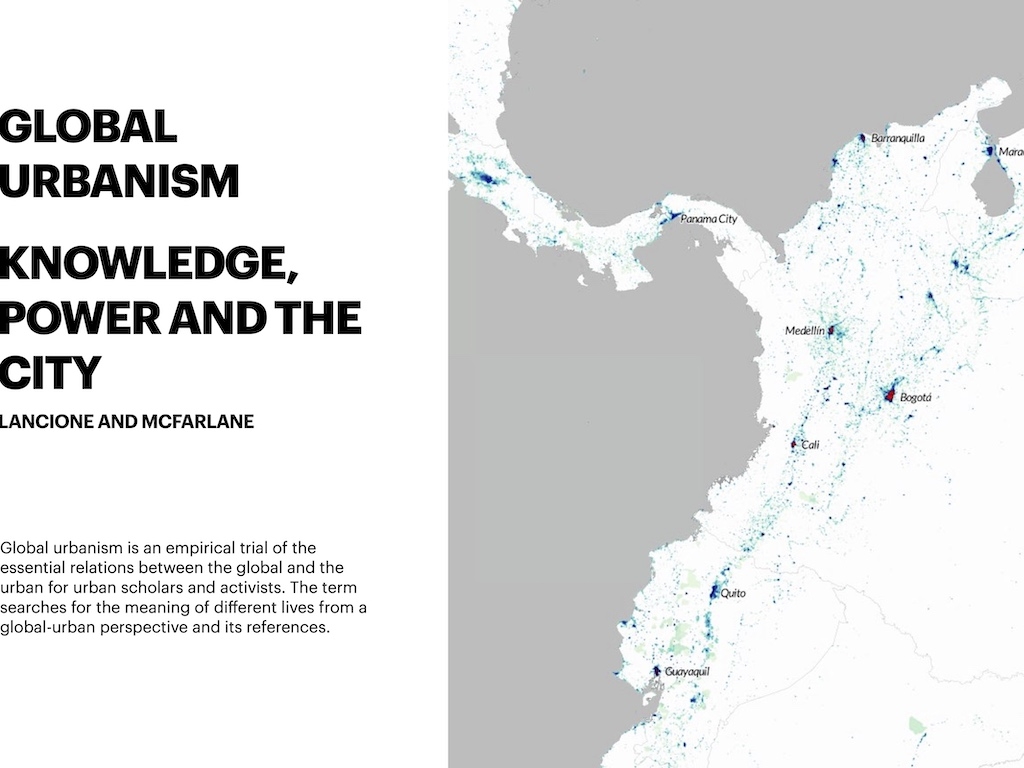

GLOBAL URBANISM

KNOWLEDGE, POWER AND THE CITY

LANCIONE AND MCFARLANE

Global urbanism is an empirical trial of the essential relations between the global and the urban for urban scholars and activists. The term searches for the meaning of different lives from a global-urban perspective and its references.

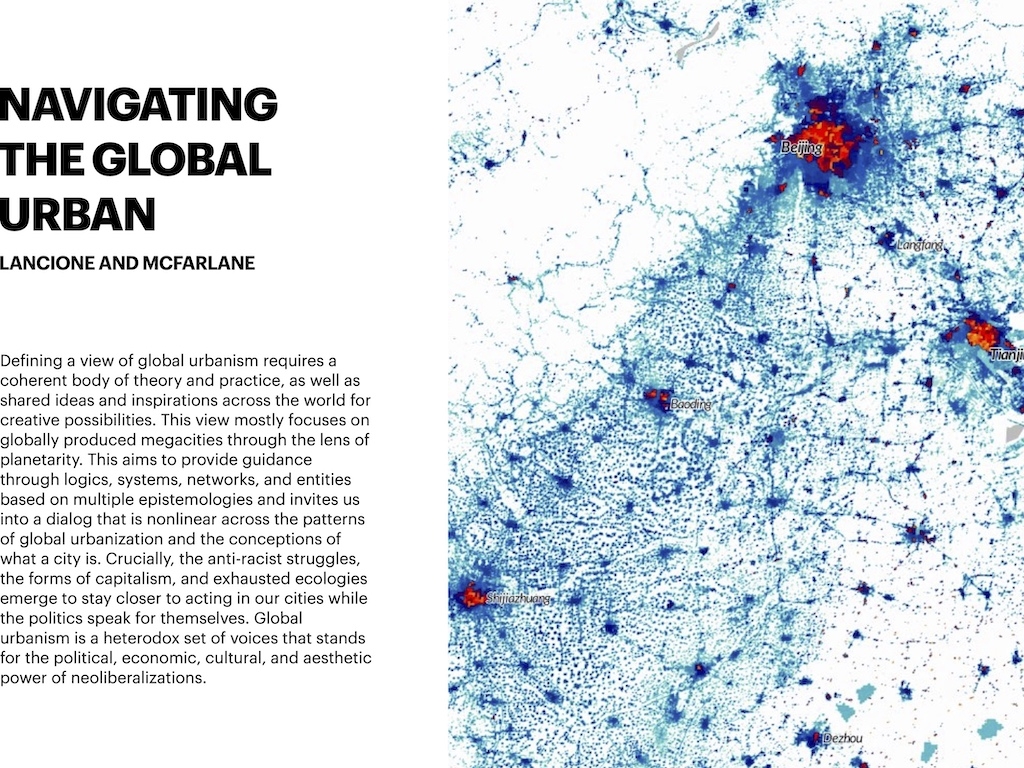

NAVIGATING THE GLOBAL URBAN

LANCIONE AND MCFARLANE

Defining a view of global urbanism requires a coherent body of theory and practice, as well as shared ideas and inspirations across the world for creative possibilities. This view mostly focuses on globally produced megacities through the lens of planetarity. This aims to provide guidance through logics, systems, networks, and entities based on multiple epistemologies and invites us into a dialog that is nonlinear across the patterns of global urbanization and the conceptions of what a city is. Crucially, the anti-racist struggles, the forms of capitalism, and exhausted ecologies emerge to stay closer to acting in our cities while the politics speak for themselves. Global urbanism is a heterodox set of voices that stands for the political, economic, cultural, and aesthetic power of neoliberalizations.

COMPARATIVE URBANISM

ROBINSON

Urban forms and processes are distributed promiscuously across perhaps quite different urban contexts, suggesting the need and potential to think about, for example, large-scale developments or satellite cities across a multiplicity of different urban contexts that speak to difference, inequality, and exclusion. In comparison with diverse cases, the experiment allows the researcher to understand the phenomenon or the problem. Urban comparativism, therefore, emerges from the practices for researchers to invent, expand, enrich, or perhaps expire a certain concept. Conceptual practices that are framed by the new subjects of urban theory are transforming the landscape of global urban studies. Transforming urban studies is radically contesting the institutional norms of international scholars production towards the comparative urban imaginations that are mobilized to a certain extent by scholars across the world.

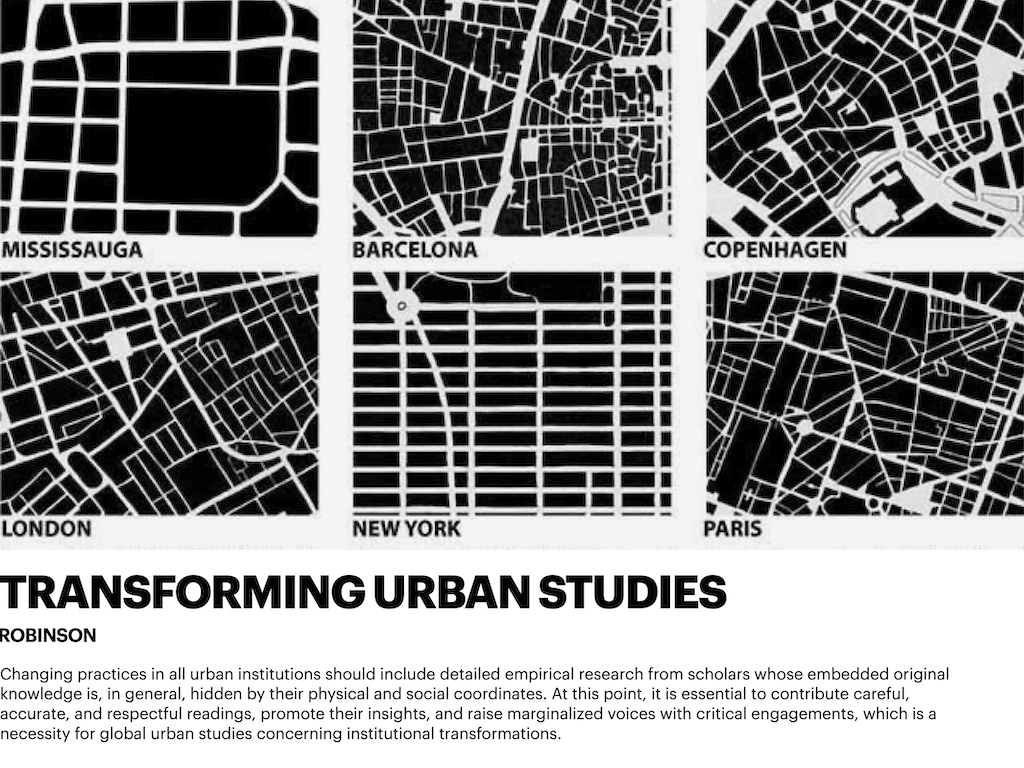

TRANSFORMING URBAN STUDIES

ROBINSON

Changing practices in all urban institutions should include detailed empirical research from scholars whose embedded original knowledge is, in general, hidden by their physical and social coordinates. At this point, it is essential to contribute careful, accurate, and respectful readings, promote their insights, and raise marginalized voices with critical engagements, which is a necessity for global urban studies concerning institutional transformations.

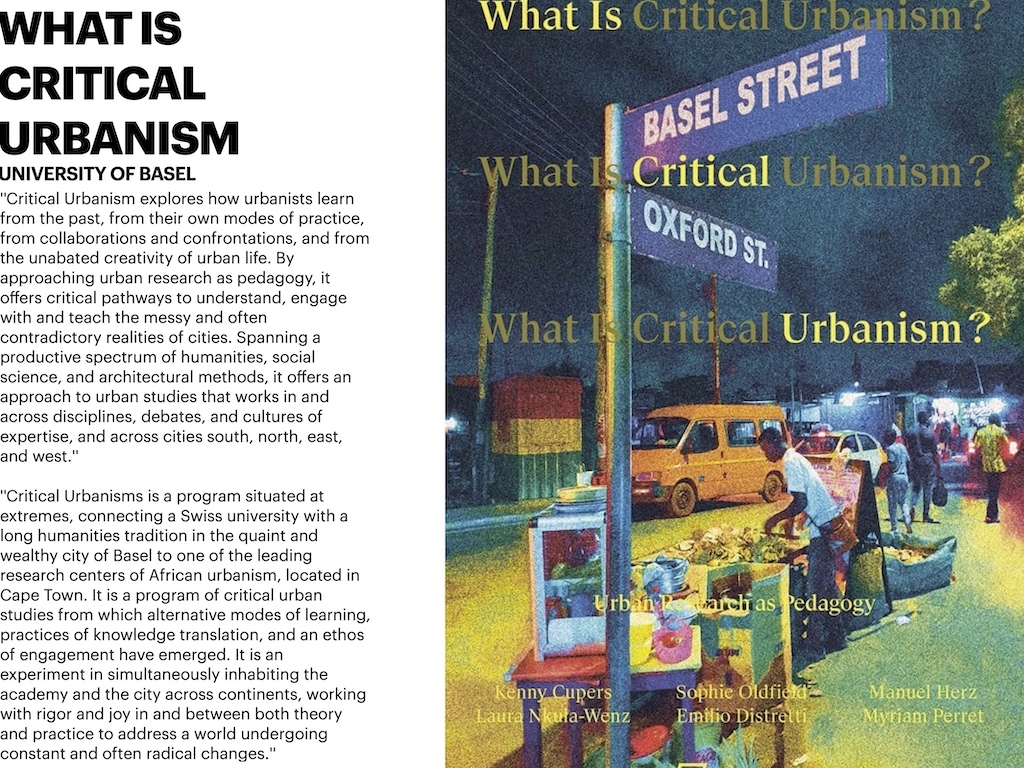

WHAT IS CRITICAL URBANISM

UNIVERSITY OF BASEL

''Critical Urbanism explores how urbanists learn from the past, from their own modes of practice, from collaborations and confrontations, and from the unabated creativity of urban life. By approaching urban research as pedagogy, it offers critical pathways to understand, engage with and teach the messy and often contradictory realities of cities. Spanning a productive spectrum of humanities, social science, and architectural methods, it offers an approach to urban studies that works in and across disciplines, debates, and cultures of expertise, and across cities south, north, east, and west.''

''Critical Urbanisms is a program situated at extremes, connecting a Swiss university with a long humanities tradition in the quaint and wealthy city of Basel to one of the leading research centers of African urbanism, located in Cape Town. It is a program of critical urban studies from which alternative modes of learning, practices of knowledge translation, and an ethos of engagement have emerged. It is an experiment in simultaneously inhabiting the academy and the city across continents, working with rigor and joy in and between both theory and practice to address a world undergoing constant and often radical changes.''

AN ETHOS OF CRITICAL URBANISM

UNIVERSITY OF BASEL

''1. Was of Knowing the City: This module explores epistemological contradictions underlying urban studies. It is interested in how disciplinary and methodological perspectives foreground multiple and at times incommensurable ways of knowing the city.

2. In Between Theory and Practice: This module examines modes of engagement in urban studies. It focuses on the political and ethical tensions arising from doing research in different urban and global settings.

3. The Urban beyond North and South: This module asks how urban studies is shaped by geographically situated claims of validity. Here, it is interrogated dominant binaries, such as North versus South.

4. The Present of the Past: This module focuses on the multiple temporalities that inhabit the city. It asks how an awareness of historical inheritances and colonial afterlives redefines contemporary urban challenges.''

KEY STATEMENTS

Aesthetic order

Social dimensions of architecture

Complex urban dynamics

Describing the world as urban

Logistical urbanism

Modern, industrial city

The violence of modern movement in cities

The meaning of decolonization today

Urban realities, government, and policies

Art cannot be ignored in cities

Rational capitalism and colonialism

Empirical research, sensing the city

Seeing the city from the perspective of another space

Culture as a specific entity

Epistemology as a way of understanding the cities

Urban phenomenon

Complex landscape of disciplines

Gender and race issues

The history of knowledge

The distinction between epistemology and ontology

There is no single way of knowing the city

The knowledge system

Movement of the body through the city

The ways gender defines the urban fabric

Conflicting nationalities

Normative ideas about citizenship

Politics in western modernist logic

History is about what changes and what stays the same

Structural racism

Universal citizenship

French power blocks of housing as the monuments of the French emperor

Corbusier: Separating different functions, home as a functional machine

Wartime mobilization, logistic operations, and industrial methods in housing

Heterosexual families, class divisions, and racist dimensions in housing

Utopias can fail

Rights for the city

Habitat's response to architectural design problematics

Marginalized residence, citizens

Architects are not heroes

Neoliberal urban policies, punishing and controlling

Heteronormativity and male dominance are two strong normative

Social dimensions of city aesthetics

The ideologies in city aesthetics

Informal places in the city

Urbanization, industrialization, and economic opportunities

The nature of the state in a postcolonial context, as a norm

The city of conflict and different realities

Cooperation and collaboration in the city

The city as a problem

The definitions of global urbanism

The real meaning of the infrastructure in the city

Invisible structures in the city based on human context

Everyday issues in the city

Design means something different for anyone

Speculative, rooted design

Bridging the gap between theory and practice

Anything outside of the academy needs theory and practice

In the academy, arguments are possible

Knowledge co-production and re-orientation in the city

European modernist ideas versus African identity

(Post)(de)(neo)colonialism

Values of white civilization

Learning the world from Africa, interconnections

The South is not only geographical space, relationships

Structural relations, space, power, and knowledge

Burjuvasist Urbanism

Sudden urbanism is not African urbanism

Public Sphere

Political practices in forensic architecture

Knowledge and connected geographical location

Heterotopia, designing for certain families and people

Masculine labor and occupation of the land

Local social dynamics resonate with global components

Modern urbanism, social reform, and extreme poverty

The Atlantic system of slave trades

Transforming human beings into things

Planetary urbanization, global conditions, and slavery

Modern state, market, production, and capitalism

Rural areas and non-humans shape the city

Postcolonial migration politics, circulation, movement

Western modernity foundation based on south

Railways and the roads of empire

Road stories and narratives of colonialism

Understanding differences and empirics

Understanding the difference of different

Materiality, special locations

Empirics of megacities

Similarity does not mean the same for cities

Hinterlands are connected to the city

Assumptions behind the hinterland

Geopolitical context shapes urban dynamics

Rural urban revolution

Demographic and postcolonial shifts in cities

Universal aspirations are not about distance

Comparative gestures in cities

The impossibility of equality

Political spectrum and injustice

Positionality embedded in research

The past is not in the past; it is still in the present

Working on heritage is about the future

Methodology, research, and pedagogy

Past, present, and future readings

City as a Living Archive

Territories of the urban

Contouring certain narratives in fascist Italy

Narratives dominated by certain actors

Heteronormativity and fascist families

Domination, certain aesthetics, and function

Social experiments in colonializing the land

The archeology of the future

Certain hierarchies through modern lenses

Ethnography as a method of research

Not setting a canon around critical urbanism

Designing better cities and spatial configurations