RESEARCH

MACHINERY: ABSTRACT SEX, PROMISES BEYOND FUNCTION

The Mutual Transition Between Man and Machine

I am searching for what is machine, not necessarily what is human. We have built a world that is, in a very large part, machine, because we have this strange double personality: we are undoubtedly part of the natural process, and yet, at the same time, we seem to inhabit this entirely different world made up of our machines. It is to this second world that we truly belong, because we have made it into our thoughts, nightmares, and fantasies. In that sense, we can only ever inhabit a life that we have already created with machines.

For a space of dialogue that is surreal, political, radical, and tender between real and imaginary across genres linked through thinking of machines as tools of cultural processes, research draws on philosophy to investigate ontological and epistemological transformations driven by machines in culture, aesthetics, and imagery memory. As a subtitle, ‘Technosexual: Machine and Philosophy’ is an experimentation and embodied research practice that creates formats for alternative modes of understanding between man and machine in aural, visual, and spatial experiences in a meditation on emotional connectivity. Exploring how machines can reconnect us with some of the innate aspects of being human and understanding how machinery shapes instinctual and intuitional perception leads us to the collective experience of survival and existence.

Among the chaos, machines are to teach us the limits of control, yet we need to embrace machines to reach the boundaries of rationality. We are, above all other things, biological organisms, which means that we have a certain “sense” for machines that the body knows how to function. Thinking about the dichotomy of the “mechanic” and the “bionic” connects us to the notion of how we perceive machines and how the perception becomes a part of our emotional infrastructure where ‘’I live with machines, against machines, and in machines.''

Challenging the boundaries of machinery and moving image in terms of process, aesthetic expression, variation on (non-)narrative forms, and representation encompasses alternate platforms, and the works produced under this platform, such as installation and exhibition, span experimental genres and performances as an artistic response to the world. The practices I have engaged with to explore the bidirectional dialogue between man and machine referees are a process between chaos and order. This leads me to the question of where I stand as an architect after such intense relations with car design during long years and enables me to embrace the relations of man and machine and the ways they construct and deconstruct one another. So, the project is a response to the (hidden) emotional dimension behind mankind and machinery, so-called abstract sex, that is often exploited by the design industry as an obsessive desire. Here, the car, as the subject of the abstract sex, considering the sensual, the corporeal, the intuitive, and the symbolic non-knowledge, comes into existence as a machinery document associated with notions like transition, manipulation, absence, and presence.

Cars as mechanical bodies create a surrealist gesture with elements of motion, improvisation, and utopia in the context of mobility as an urban infrastructure. Over the automobility, as a gap between reality and fiction, examining the form and aesthetics of movement within such structures where intuition, presence, and consciousness play an essential role leads us to the idea of the city as ‘function of movement’ (Urry J., 2000).

''We use ‘automobility’ here in order to capture a double sense. On the one hand, ‘auto’ refers reflexively to the humanist self, such as the meaning of ‘auto’ in notions like autobiography or autoerotic. On the other hand, ‘auto’ often occurs in conjunction with objects or machines that possess a capacity for movement, as expressed by terms such as automatic, automaton, and especially automobile. This double resonance of ‘auto’ is suggestive of the way in which the car driver is a ‘hybrid’ assemblage, not simply of autonomous humans but simultaneously of machines, roads, buildings, signs, and entire cultures of mobility (Haraway, 1991; Thrift, 1996: 282-4). We outline a manifesto for the analysis of ‘auto’ mobility that explores this double resonance of autonomous humans and autonomous machines only able to roam in certain time-space scapes.'' (The City and the Car: Urry J., Sheller M., 2000)

Outcome

Research aims for creative as well as intellectual experiences in interdisciplinary approaches and collective consciousness. For an experimental methodology for the research, issues will be discussed in speculative manners dealing with utopic, dystopic, and heterotopic conjunctions. It is aimed at manifesting semiotic archetypes that borrow different qualities from human and machine interactions.

The research is a creative process that will apply design as research. It will use lateral and intuitive methods ‘through’ design that produce more debate by being further developed in discussions between theory and practice.

In the last few decades, blurring the boundary between reality and fiction has become a subject that has become increasingly popular within new academic fields. In fact, the concept of faction, a hybrid concept between documentary and fiction, or reality and fiction, is a product of this process. We are going through a period in which the boundaries of both forms are blurred, and it is getting hard to define what is real and what is fiction.

Apart from functionality, machines are ambiguous, uncertain, and fascinating. Conceptual research in this context, especially those not designed to be built, produces knowledge rather than questions. In this sense, the project provides reflections on what is there—to imagine something different, to question rather than describe—that avoids the science/art and the qualitative/quantitative splits and allows freedom.

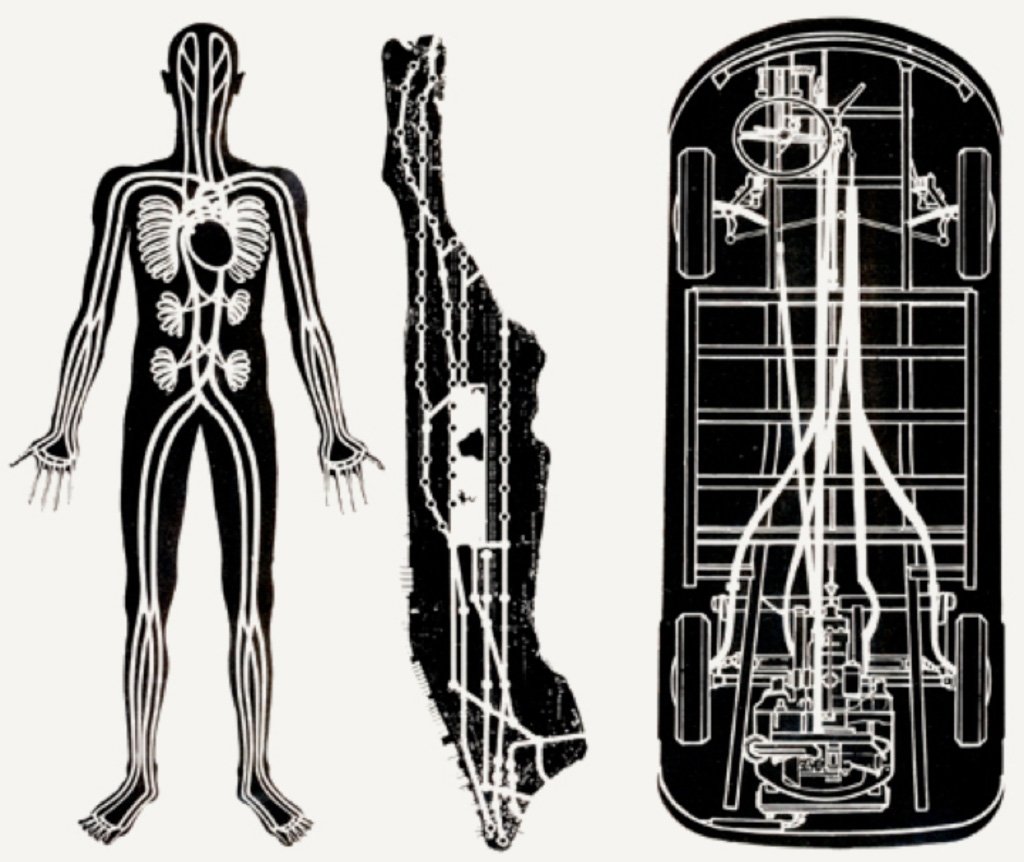

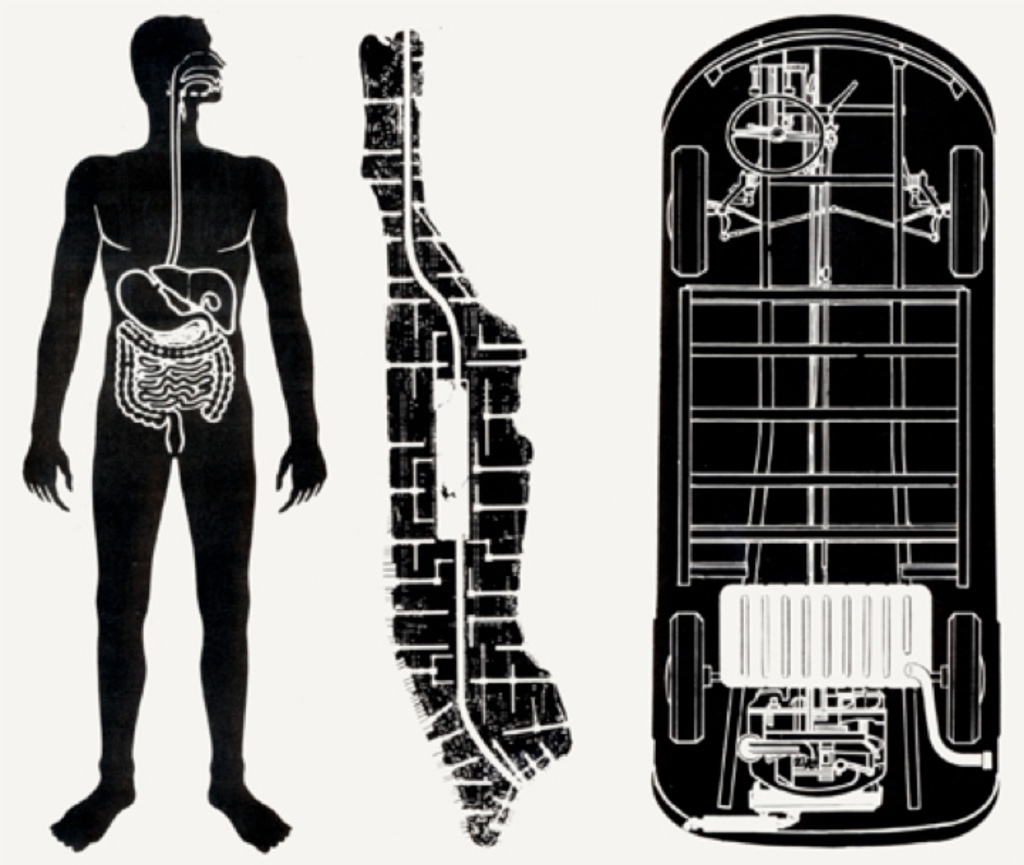

O.M. Ungers’ City Metaphors (1976) relate bodies, cities, and mechanisms through their systems of structure, circulation, and energy.

ANTHROPOMORPHISM AND MECHANOMORPHISM

The Two Faces of Humanity

Akova Fırat

Poedat Collective Philosophy Conference, Smyrna, Turkey, c. 2015

It is all about the ambiguity of the “human machine." Mechanomorphism, the attribution of machine characteristics to humans, is a culturally derived metaphor that presently dominates the cognitive sciences. The relation between anthropomorphism and mechanomorphism can pose a particular case for the human body and inquire, “Can machines feel?”

We see colors, hear sounds, and feel textures; the abstract nature and the experimental diagnostic of mechanomorphism intend to draw out the unseen interactions between humans and machines in a particular sense.

The endeavor here to define the ontological limit of the human body constituted the intersection of philosophical, biological, and theological initiatives. Aside from epistemological discussions, differentiating between body and machine has become a detrimental habit, a metaphysical tradition, and even an oppressive ideology. Immanence has been regenerated throughout history by means of discourse, politics, and aesthetics over two concepts: the body and the machine.

The machine is classified as separate from the body and used as a metaphor to highlight corporeality. When the body is thought to be teleological, in other words, when the status of being a vehicle for something is assimilated with the body, it is argued that the body is a type of machine; the limit drawn for the body cannot be expanded towards the limit of the machine; conversely, the body is retracted to the limit of the machine. According to Georges Canguilhem, likening body parts such as the stomach, veins, and muscles to tools like heating chambers, hydraulic tubes, cables, and cords, the body is transformed into a machine to satisfy the ideologies that exalt the technique. As a matter of fact, it is not a coincidence that Aristotle described the bodies of the slaves as “moving machines” and that René Descartes laid the foundation of mechanical philosophy, or consciousness, at the beginning of capitalism.

The fact that all elements and processes of the body can be found in the machine creates an extraordinary sense of adventure and makes us experience emotional exaltation. The body is the cause and the result, the subject and the object, the beginning and the end, whose limits have not been able to be determined. The body is more than an input-output space; it is a structure that can consciously or unconsciously penetrate into the machine. The outcome of the relationship between the body and the machine is that the body is not equivalent to the machine, but the limit of the machine is at the same time the limit of the body.