COURSE

CRITICAL CARTOGRAPHY

University of Basel, Urban Studies, MA Critical Urbanisms, Fall 2023

Alaa Dia

FIELDWORK

October 13, 2023

OVERVIEW

A critical component of interdisciplinary exploration into spatial politics

''This excursion enables us to delve into the peculiar border dynamics between Germany and Switzerland.

The journey encompasses

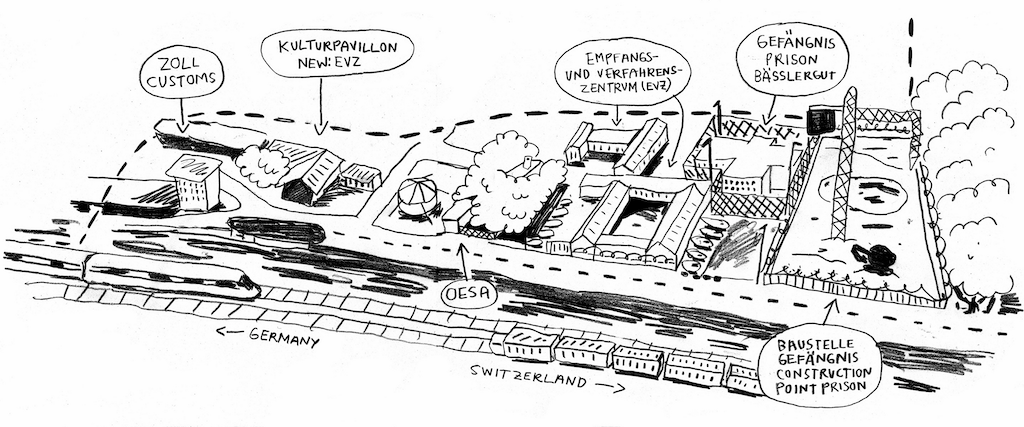

German Railway Site Visit, Badischer Bahnhof: Observing the distinct borders, offices, surveillance controls, and performative aspects of the border, exploring both the interior and exterior of the site to understand the unique cross-border relations.

Bässlergut Detention Facility and Asylum Centre: A walking tour around the prison, unraveling the intricacies of the relationship between the prison, asylum center, and borders.

Checkpoint Border Visit: Examination of a primary checkpoint to understand the borders.

Objectives

This fieldwork is conceived as a collective scholarly endeavor to:

Engage in a methodological experiment to elucidate the spatial politics of Basel.

Facilitate the articulation of a focal theme or site for a culminating critical essay and cartographic project.

Employing a multi-modal methodological approach for site documentation, which may include participant observation, cartographic sketching and drawing, archival research, photographic documentation, and analysis of satellite images.’

Collecting supplementary data, which will serve as empirical support for the arguments advanced in further projects.

Having an invaluable opportunity to ground our theoretical inquiries in real-world observation and analysis.’' Alaa Dia

MA Critical Urbanism-University of Basel

MA Critical Urbanisms - Instagram

POST-FIELDWORK

CRITICAL ESSAY

Prepared for one of the term assessments

FIELDWORK

An investigative journey in active participation

GRAY ZONE

EXCURSION: BORDER, POWER AND SPACE

PERFORMATIVE

CROSS-BORDER RELATIONS

The fieldwork on October 13th was an important process to experience the exceptional border dynamics between Switzerland and Germany and to observe the ongoing complex relations between prison, asylum, and border, which are shaped around a building that can still be considered within the city. This helps us examine the daily border practices around control points.

Exploring all these non-physical, intangible, and invisible dynamics surrounding this border, which are not noticed at first, pushes us to think about the real meanings of being exceptional, being on edge, and being restricted. At the same time, it forces us to think about scale, transition, and social dimensions in the name of the social dimensions of space, which leads us to re- question many points about the urban landscape. While examining all these complex spatial patterns that occur within a paradoxical structure, we find ourselves looking at a picture mixed with identity, obstacles, and impasses from the point of view of the politics of space. This powerful influence, which pushes us to understand our own limits, appears with many other emotions, such as freedom, security, and anxiety.

BORDERS ON THE AIR

A GRAY NON-SPACE

Perhaps the strongest phenomenon that can be felt during this experience is that power, space, and resistance are limited, controlled, and transformed into a political discourse. In this sense, borders, beyond being mere physical areas or definitions that seem passive and neutral, also play a transformative role in urban space as social organization tools. At this point, I asked myself the following: Can we talk about a certain kind of aesthetic of the border, a unique existence, and a specific geographical formation?

Borders are areas that construct, represent, and change our relationship with the city; they are a kind of interface where the first interaction between the city and us begins; they are active places. The border is also a narrative; it is a powerful context in which human stories are shaped in cultural, political, and socio-economic contexts; they contain a social dimension. In this sense, borders should be seen as critical areas of struggle beyond being tools of hegemony legitimized in the name of power and control.

MEASURES

TERRITORIAL AND ARADOXICAL CONFLICTS

Borders also serve other powers of control; they try to impose a new reality, erase the traces of the past, and draw the boundaries of a certain region as an area of intervention. They can also be defined as marginalized, violent, and eerie spaces on an urban scale. In this sense, I question myself: Can we talk about spatial ethics regarding borders?

What exactly do all these borders have to do with the urban panorama of Basel, and what kind of semantic landscape do they form for the city? All these local relationships contain important information about how power relations come to life in a spatial sense in our immediate environment. Thinking beyond the border, examining the dynamic relationship of the border with the socio-political dimensions of space, and noticing the strong character of the border within the urban fabric will create a kind of critical path that defines power relations, ethical elements, and social consequences.

BADISCHER BAHNHOF: GERMAN RAILWAY STATION

MATERIALITY OF BORDERS

This highly specific border interaction between Switzerland and Germany involves unique and complex dynamics in terms of distinct borders, control points, and the way the border is performed. While this set of relationships makes us question what exactly the border means in materiality, it also makes us think about how we understand the border with the ''things'' that make it up, in the context of a train station, both inside and outside. Most importantly, it asks what the border actually represents and in what form the border defines a physical and psychological space beyond being a line.

This structure, which operates under the control of German border units in a territory belonging to Switzerland, shows us that this uncertainly defined gray area contains different social forms, power relations, and feelings beyond being just a physical border.

The fact that German units, especially the police, are positioned and expressed as the dominant power in this field causes people to feel different emotions, sensitivities, and contradictions. This also means that a country reveals itself, makes itself visible, and comes into being in another country. While this entire structure, beyond being symbolic, makes spatial mechanisms visible, it also causes the formation of a new sensory area in the name of security, distances, and obstacles.

The question of how the border is performed in this train station leads us to think about the actors of this performance: police, control units, customs, passengers, and indescribable feelings of anxiety, fear, and danger. In such a tense interaction area, one can immediately feel that they are in an area where even the air is controlled beyond physical boundaries. This hybrid space, which perhaps does not exactly seem like a border, actually contains stronger, harsher, and more brutal political, social, and spatial relations than a border should be; this is an exceptional area. Agamben helps us analyze the semantic relations that this field of exception has and says that the exception explains the general and itself; and when one really wants to examine the general, one only has to look around to find a real exception.

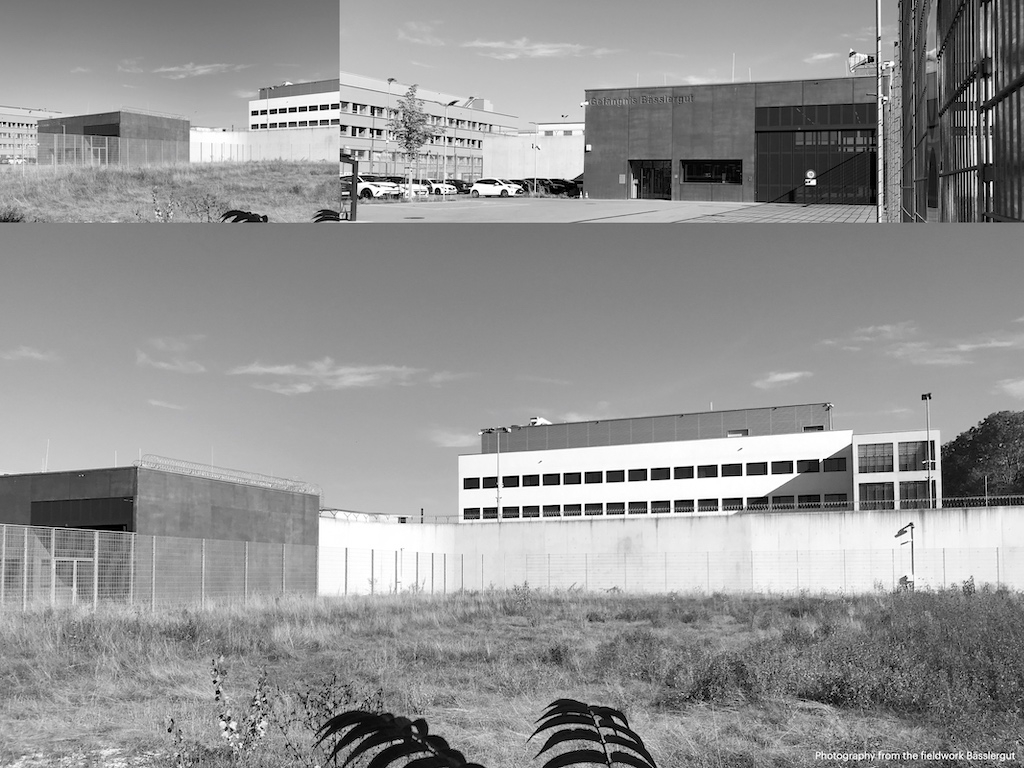

BÄSSLEERGUT

DETENTION FACILITY, ASYLUM CENTER

Walking around a prison building always evokes eerie feelings. The same can be said for this building; this extended space, where the complex relations between prison, asylum center, and border are rearranged, appears as a unique special zone, a weaponized landscape, and a panoramic space where people are taken in or out. This situation brings into question the high walls, fences, and distance of a destructive building in its relationship with the city. I ask myself: How are we, those of us outside, affected by all this when we pass by such a building? Examining the layered structure of a prison building leads us to confront both its physical and psychological dimensions, which actually seem like the struggle of the border, of being inside and being outside.

The fact that this building is located on the Swiss- German border raises another question: why does Switzerland want to integrate a prison building into Germany’s urban landscape, and what does its presence create for those living around it? This gray area, the border line between existent and nonexistent, actually defines a line as clear as black and white, perhaps drawn with much thicker lines on behalf of Switzerland: We positioned our worst building to be close to you; we made a building that is not desirable for anyone but visible to you. We like our border with you as much as we like this building.

This gray area is a non-place, an extended space where the city is ending, life is decreasing, and sounds are disappearing. Unlike the invisible boundary in the air, all the paradoxes, conflicts, and obstacles of this place are highly visible. It seems that it remains unclear for everyone here what kind of identity is attributed to this spatial organization, what kind of physical and emotional thresholds are attached, and to what extent it can be considered as belonging to the city. Agamben points out that one of Foucault's most persistent features is his exploration of the concrete ways in which power penetrates the bodies and lifestyles of subjects. Mark B. Salter adds that borders are a unique political space where both sovereignty and citizenship are exercised.

What exactly do we know about prisons? These buildings appear as architectural formations designed with high walls, countless cameras, and boundaries other than security; they appear as silent, non-existent spaces shaped between freedom and imprisonment, where space is associated with crime. Is there a perfect prison? For the architects, these buildings, reinterpreting individual and social space, being inside and outside, appear as a kind of prosthetic space added to the space with their unique materials; these lonely buildings, which cannot find their place on an urban scale, lack a sense of belonging, and do not want to interact with their environment, reveal this uncertainty, grayness, and contradiction, like the borders themselves. This area, shaped by contrasts, creates its own scale on behalf of the social dimensions of the space, and this scale destroys the human scale.

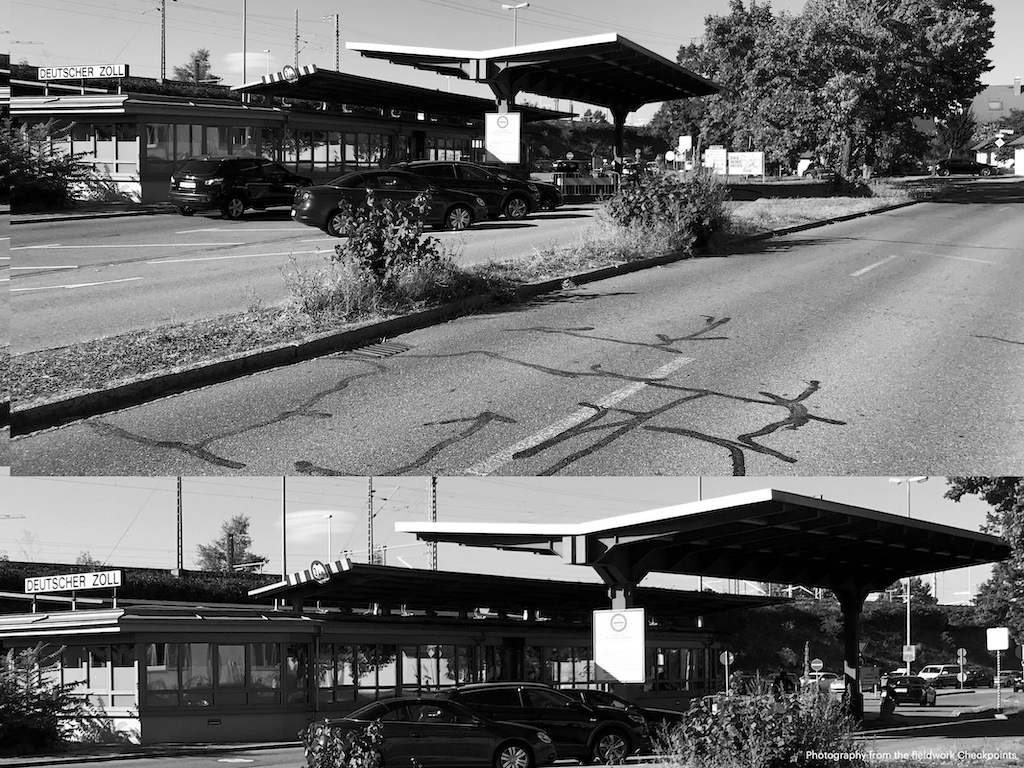

CHECKPOINT BORDER

FRAGMENTS OF ORDER

Another place where it is difficult to understand borders is checkpoints. These areas not only contain political messages but also convey symbolic, spatial, and social messages that the state uses to make itself visible.

These checkpoints on the borders, located between Switzerland and Germany and open to cars, bikes, and pedestrians, are fields of power that go beyond determining the borders between the two countries. This power creates its own dynamics in the secret relationships between checking, monitoring, and setting rules more frequently. This is a field of alignment, order, and law-making.

Agamben says that the rule requires a homogeneous environment; there are no rules that can be applied to chaos; an order must be established for the legal order to gain meaning. Mark B. Salter adds that border officers and state bureaucrats play a critical role in determining where, how, and on whose body the border will be applied. And Balibar continues that by marking a border, precisely to define a region, to delimit it, and thus to register the identity of that region or to give it an identity.