COURSE

MATERIAL INVESTIGATIONS

CONCRETE IN SWITZERLAND

University of Basel, Urban Studies, MA Critical Urbanisms, Fall 2023

Fabrizio Furiassi

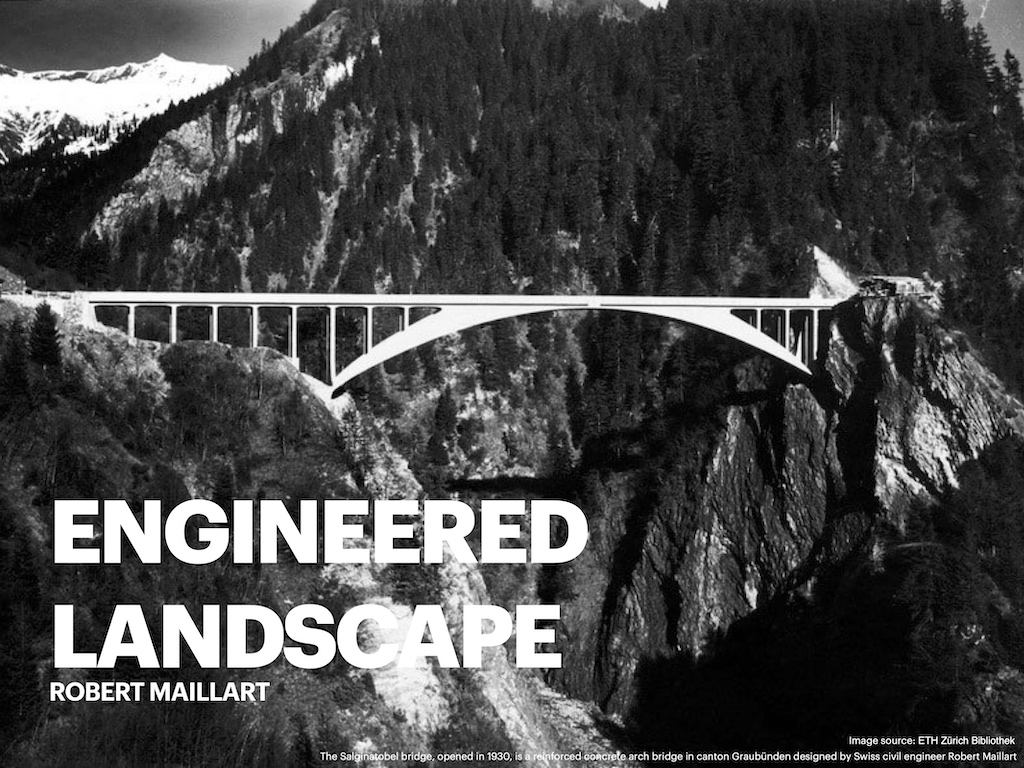

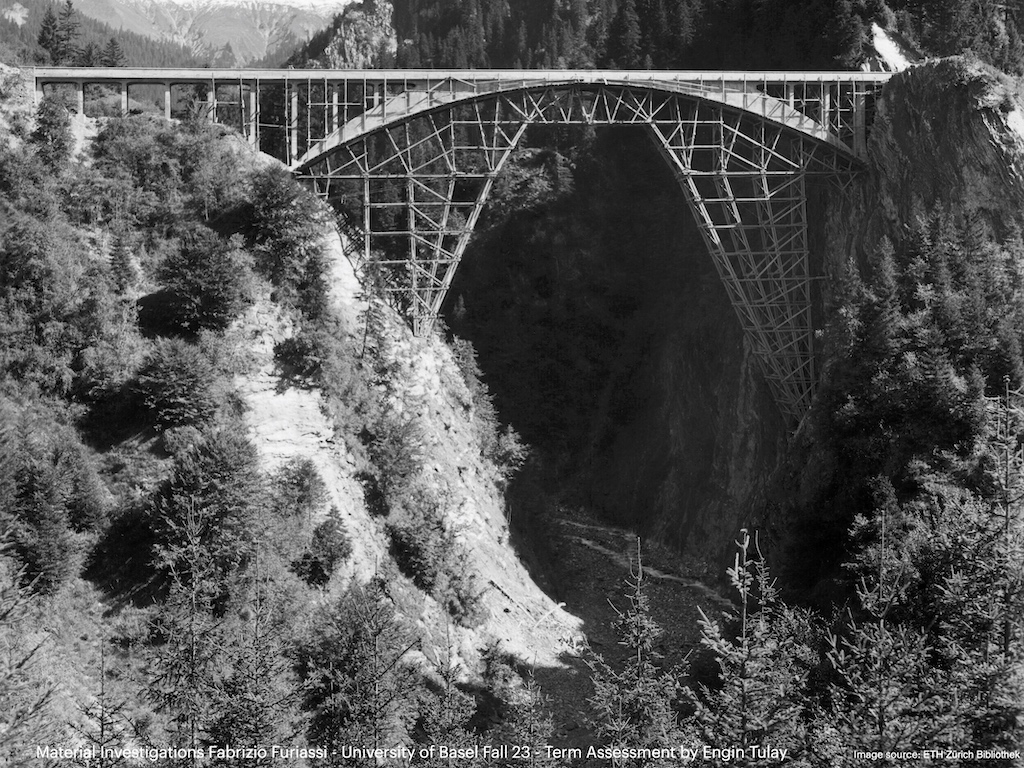

ROBERT MAILLART - SALGINATOBEL BRIDGE

The project is rooted in the specific features of the Salginatobel Bridge and contextualized within the structural practice prevalent in the first quarter of the 20th century, intrinsically connected with ways of constructing with concrete at that time, and presents Robert Maillart’s structural design.

It questions how the material acts in relation to nature and how people are positioned to a certain degree in this connection in terms of understanding it. The Salginatobel Bridge by Robert Maillart is given as an example to observe this re-production with its certain characteristics of concrete. How does the designed landscape find its new meaning through the materials used in the context of infrastructure? Does the concrete act on its own, or does the dialect between nature and the concrete flow together? In the process of spatial transition through materials, the exchange between people and nature takes place over the transformation of the landscape through concrete.

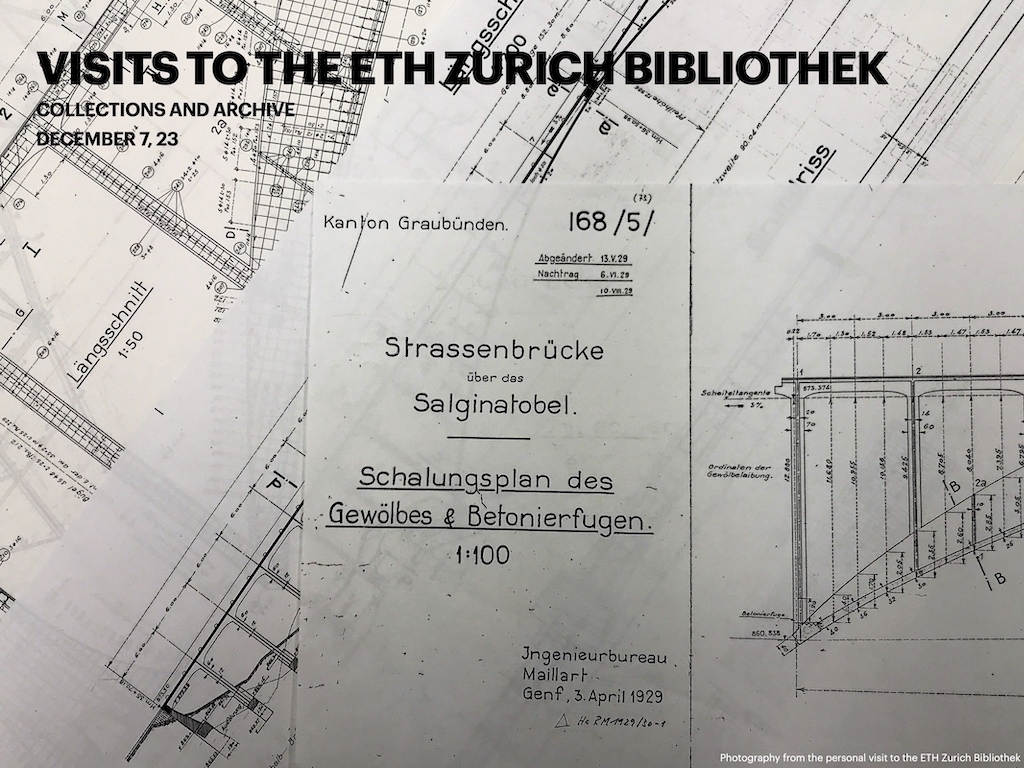

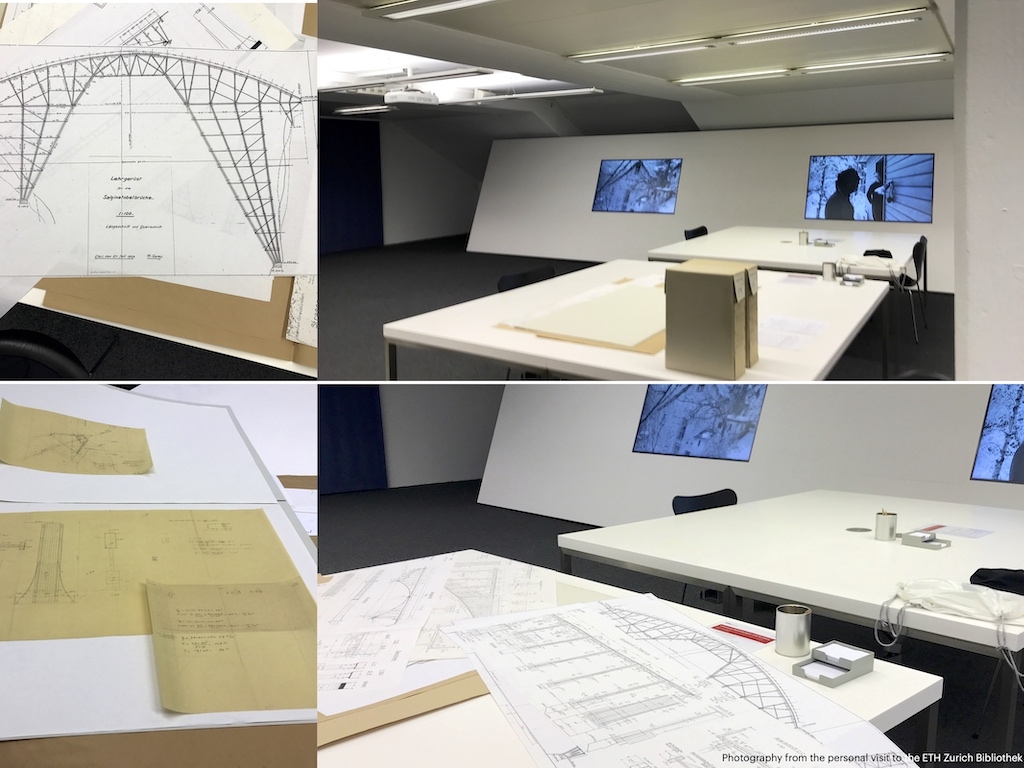

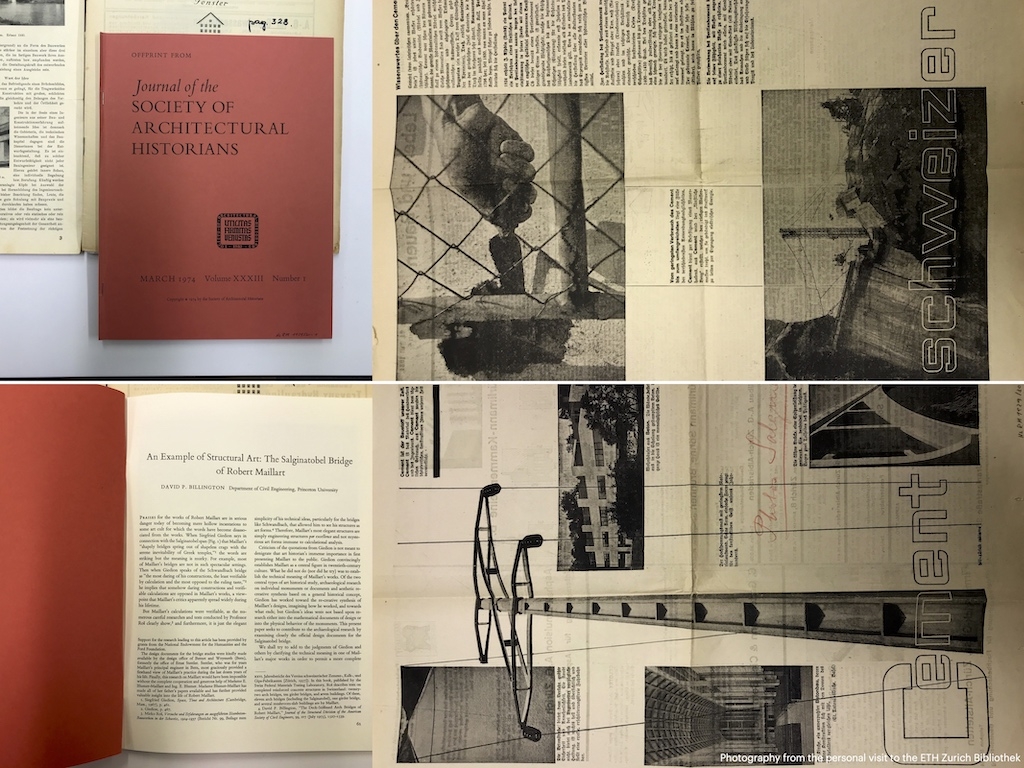

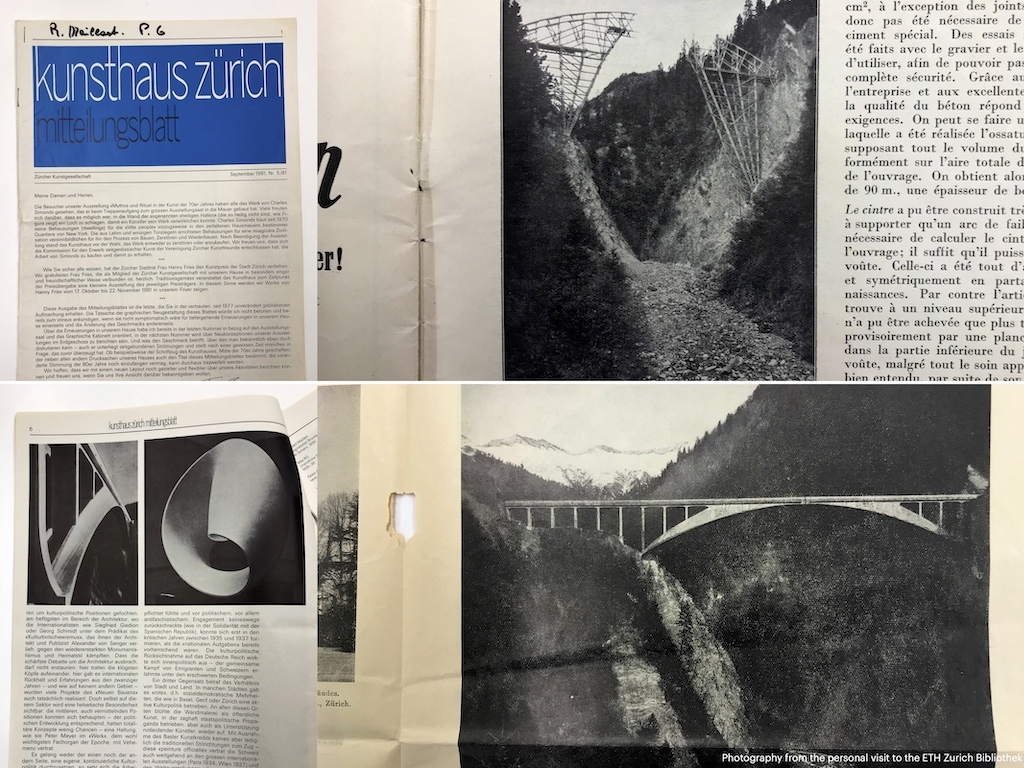

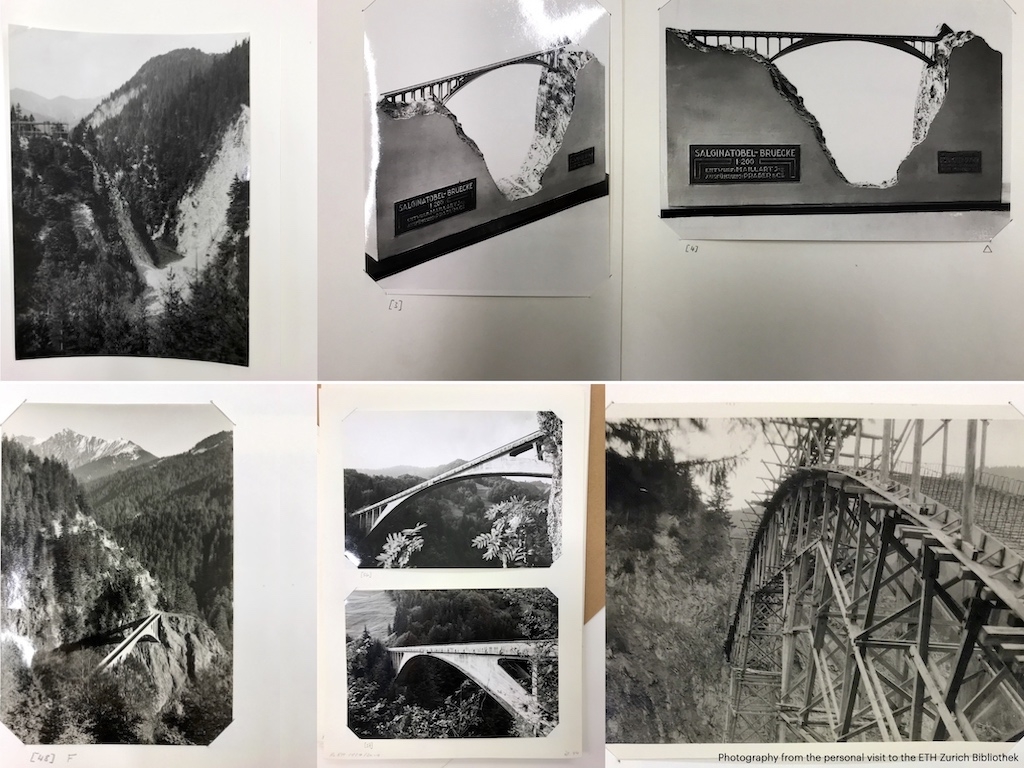

These features of Maillart’s work are an attempt to summarize what contributes to the specific nature of these works of concrete in Switzerland. The contents are supplemented by visual materials based on personal visits to the bridge, the ETH-Bibliothek Collections and Archive, and descriptions that can be found online at the ETH- Bibliothek’s and Salginatobel Bridge’s website.

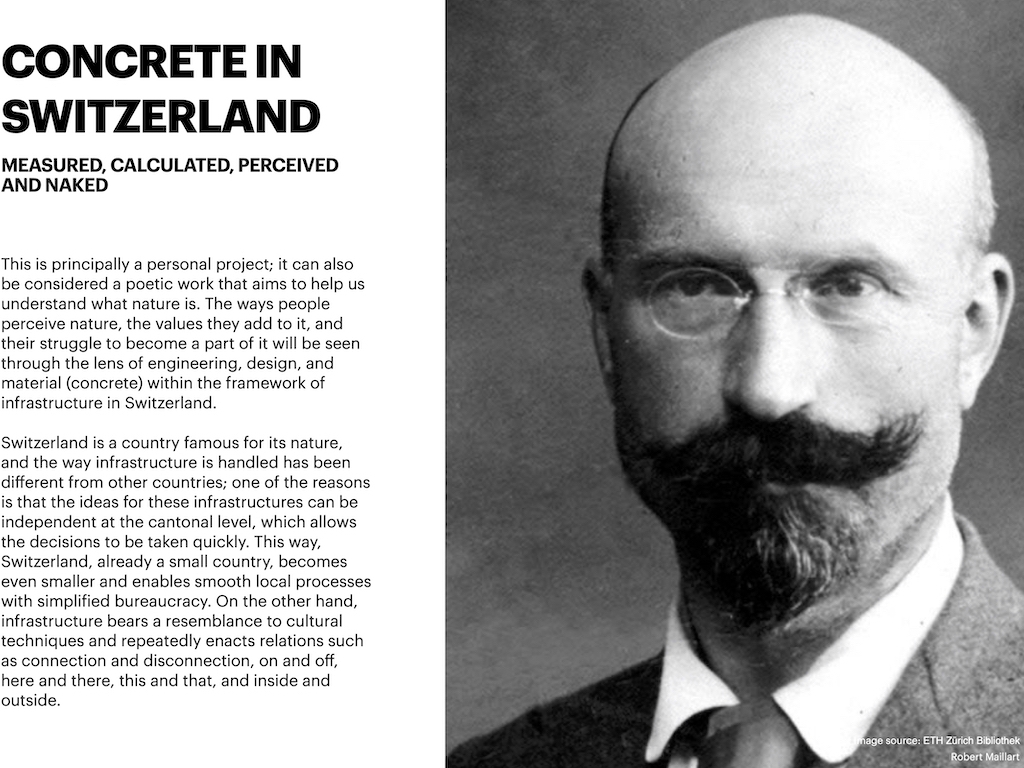

*Robert Maillart was born in 1872, and he practiced engineering between 1894 and 1940.

*American Society of Civil Engineers declared the Salginatobel Bridge a ''world monument’’. In a world-wide survey, the renowned British trade journal voted the Salginatobel Bridge the most beautiful bridge of the century.

MA Critical Urbanism-University of Basel

MA Critical Urbanisms - Instagram

ENGINEERED LANDSCAPE - MADE IN CONCRETE

Prepared for one of the term assessment

ROBERT MAILLART

SALGINATOBEL BRIDGE

MEASURED, CALCULATED, PERCEIVED AND NAKED

This is principally a personal project; it can also be considered a poetic work that aims to help us understand what nature is. The ways people perceive nature, the values they add to it, and their struggle to become a part of it will be seen through the lens of engineering, design, and material (concrete) within the framework of infrastructure in Switzerland.

Switzerland is a country famous for its nature, and the way infrastructure is handled has been different from other countries; one of the reasons is that the ideas for these infrastructures can be independent at the cantonal level, which allows the decisions to be taken quickly. This way, Switzerland, already a small country, becomes even smaller and enables smooth local processes with simplified bureaucracy. On the other hand, infrastructure bears a resemblance to cultural techniques and repeatedly enacts relations such as connection and disconnection, on and off, here and there, this and that, and inside and outside.

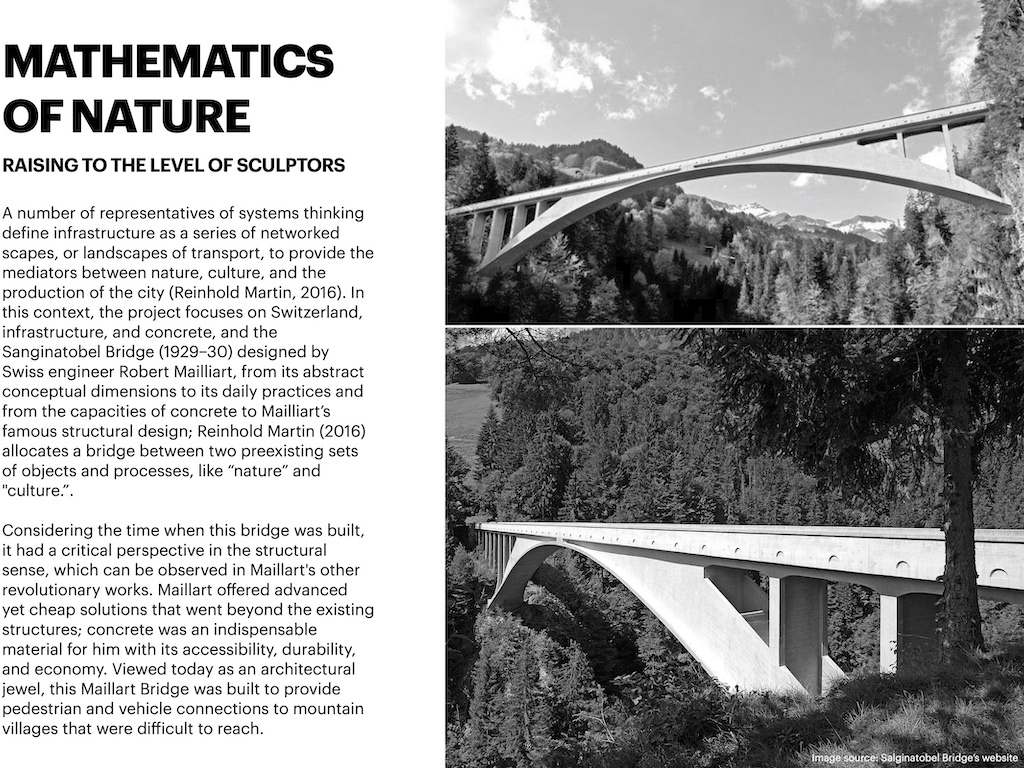

MATHEMATICS OF NATURE

RAISING TO THE LEVEL OF SCULPTORS

A number of representatives of systems thinking define infrastructure as a series of networked scapes, or landscapes of transport, to provide the mediators between nature, culture, and the production of the city (Reinhold Martin, 2016). In this context, the project focuses on Switzerland, infrastructure, and concrete, and the Sanginatobel Bridge (1929–30) designed by Swiss engineer Robert Mailliart, from its abstract conceptual dimensions to its daily practices and from the capacities of concrete to Mailliart’s famous structural design; Reinhold Martin (2016) allocates a bridge between two preexisting sets of objects and processes, like “nature” and "culture.”.

Considering the time when this bridge was built, it had a critical perspective in the structural sense, which can be observed in Maillart's other revolutionary works. Maillart offered advanced yet cheap solutions that went beyond the existing structures; concrete was an indispensable material for him with its accessibility, durability, and economy. Viewed today as an architectural jewel, this Maillart Bridge was built to provide pedestrian and vehicle connections to mountain villages that were difficult to reach.

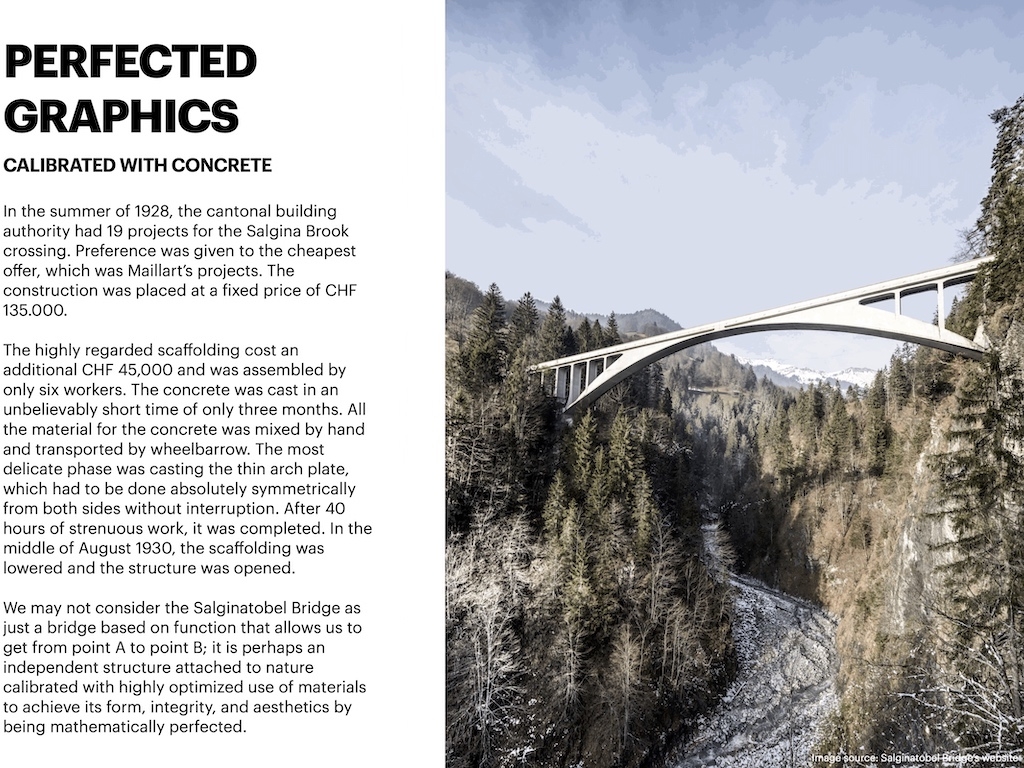

PERFECTED GRAPHICS

CALIBRATED WITH CONCRETE

In the summer of 1928, the cantonal building authority had 19 projects for the Salgina Brook crossing. Preference was given to the cheapest offer, which was Maillart’s projects. The construction was placed at a fixed price of CHF 135.000.

The highly regarded scaffolding cost an additional CHF 45,000 and was assembled by only six workers. The concrete was cast in an unbelievably short time of only three months. All the material for the concrete was mixed by hand and transported by wheelbarrow. The most delicate phase was casting the thin arch plate, which had to be done absolutely symmetrically from both sides without interruption. After 40 hours of strenuous work, it was completed. In the middle of August 1930, the scaffolding was lowered and the structure was opened.

We may not consider the Salginatobel Bridge as just a bridge based on function that allows us to get from point A to point B; it is perhaps an independent structure attached to nature calibrated with highly optimized use of materials to achieve its form, integrity, and aesthetics by being mathematically perfected.

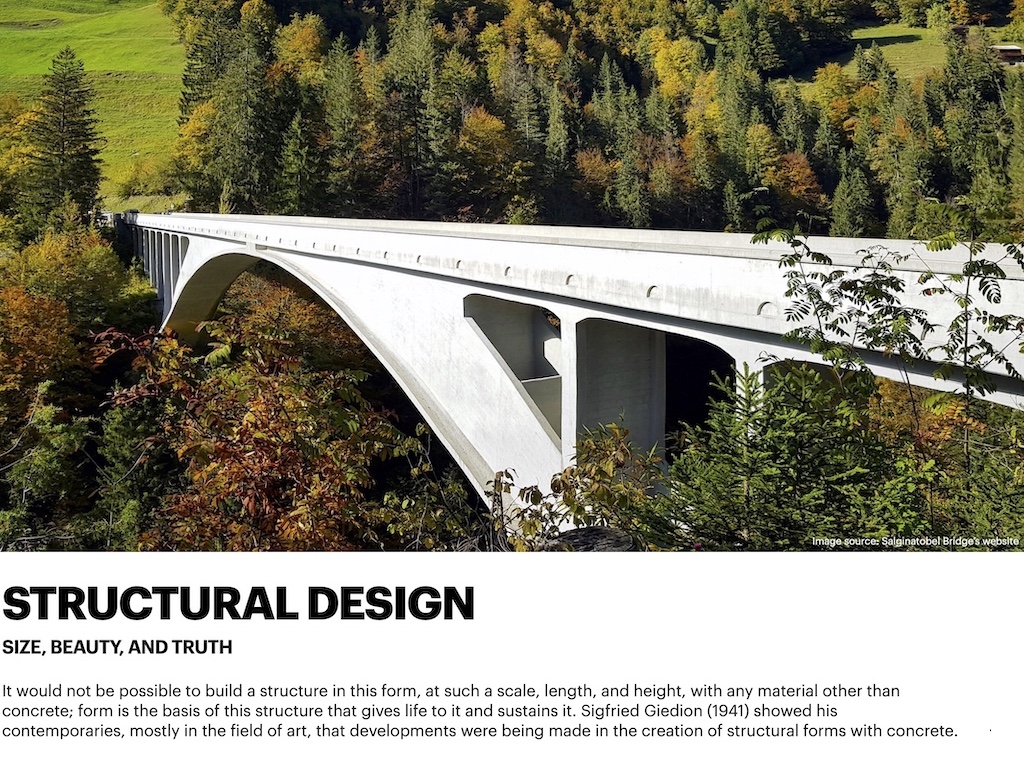

STRUCTURAL DESIGN

SIZE, BEAUTY, AND TRUTH

It would not be possible to build a structure in this form, at such a scale, length, and height, with any material other than concrete; form is the basis of this structure that gives life to it and sustains it. Sigfried Giedion (1941) showed his contemporaries, mostly in the field of art, that developments were being made in the creation of structural forms with concrete.

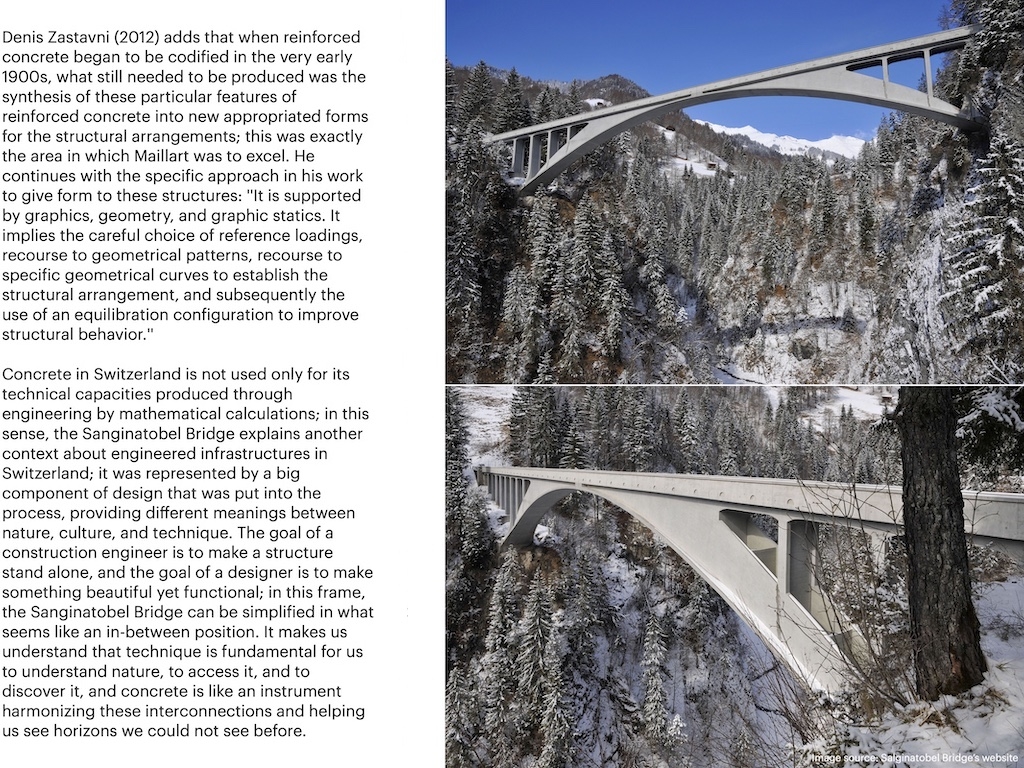

Denis Zastavni (2012) adds that when reinforced concrete began to be codified in the very early 1900s, what still needed to be produced was the synthesis of these particular features of reinforced concrete into new appropriated forms for the structural arrangements; this was exactly the area in which Maillart was to excel. He continues with the specific approach in his work to give form to these structures: ''It is supported by graphics, geometry, and graphic statics. It implies the careful choice of reference loadings, recourse to geometrical patterns, recourse to specific geometrical curves to establish the structural arrangement, and subsequently the use of an equilibration configuration to improve structural behavior.''

Concrete in Switzerland is not used only for its technical capacities produced through engineering by mathematical calculations; in this sense, the Sanginatobel Bridge explains another context about engineered infrastructures in Switzerland; it was represented by a big component of design that was put into the process, providing different meanings between nature, culture, and technique. The goal of a construction engineer is to make a structure stand alone, and the goal of a designer is to make something beautiful yet functional; in this frame, the Sanginatobel Bridge can be simplified in what seems like an in-between position. It makes us understand that technique is fundamental for us to understand nature, to access it, and to discover it, and concrete is like an instrument harmonizing these interconnections and helping us see horizons we could not see before.

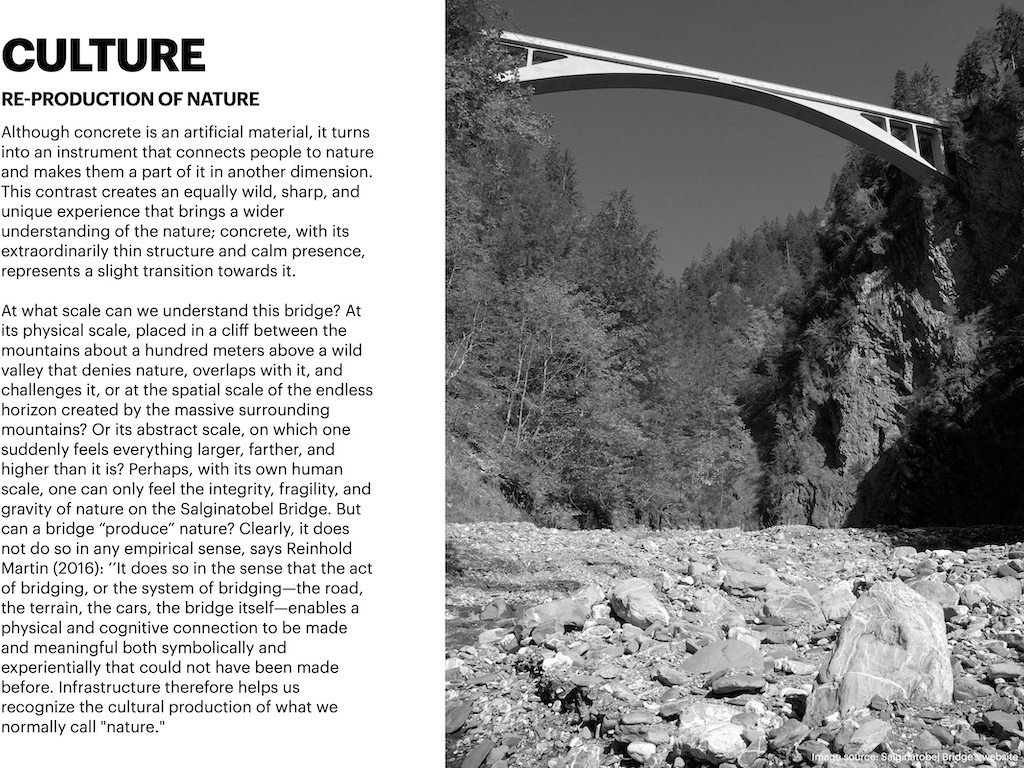

CULTURE

RE-PRODUCTION OF NATURE

Although concrete is an artificial material, it turns into an instrument that connects people to nature and makes them a part of it in another dimension. This contrast creates an equally wild, sharp, and unique experience that brings a wider understanding of the nature; concrete, with its extraordinarily thin structure and calm presence, represents a slight transition towards it.

At what scale can we understand this bridge? At its physical scale, placed in a cliff between the mountains about a hundred meters above a wild valley that denies nature, overlaps with it, and challenges it, or at the spatial scale of the endless horizon created by the massive surrounding mountains? Or its abstract scale, on which one suddenly feels everything larger, farther, and higher than it is? Perhaps, with its own human scale, one can only feel the integrity, fragility, and gravity of nature on the Salginatobel Bridge. But can a bridge “produce” nature? Clearly, it does not do so in any empirical sense, says Reinhold Martin (2016): ‘’It does so in the sense that the act of bridging, or the system of bridging—the road, the terrain, the cars, the bridge itself—enables a physical and cognitive connection to be made and meaningful both symbolically and experientially that could not have been made before. Infrastructure therefore helps us recognize the cultural production of what we normally call "nature."

RESOURCES

Reinhold, M. (2016). Infrastructure and Mediapolitics. University of Minnesota Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1g69w99.14

Zastavni, D. (2012). Maillart’s Practices for Structural Design: ETH-Bibliothek’s Virtual Exhibition. Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. https:// dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal%3A106876/datastream/PDF_01/view

Fairclough, C. (2018). Discovering the Art of Civil Engineering. Comsol Blog. https://www.comsol.de/blogs/happy-birthday-robert-maillart/ Robert Maillart. Die Brücken. http://www.bernd-nebel.de/bruecken/index.html?/bruecken/2_pioniere/maillart/maillart.html

Conzett, J. (2014). Robert Maillart in der Ukraine. Das Guckloch Nr. 2/2014. https://www.ingbaukunst.ch/file/436/Guckloch_02-2014.pdf Billington, David P. (1997). Robert Maillart, Builder, Designer and Artist. Cambridge University Press, p. 331, ISBN 9780521571326

Bruun, Edvard P.G. (2014). Robert Maillart: The Evolution of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Forms. University of Toronto, Canada. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/ Edvard-Bruun/publication/328725279_Robert_Maillart_The_Evolution_of_Reinforced_Concrete_Bridge_Forms/links/5bdde24f4585150b2b9d3ae1/Robert-Maillart-The- Evolution-of-Reinforced-Concrete-Bridge-Forms.pdf

Museum of Modern Exhibits Swiss Bridges Remarkable for Beauty and Engineering: Robert Maillart: Engineer. MoMA. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3212

Salginatobel Bridge Official. https://www.salginatobelbridge.co

Scientist: Robert Maillart. https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/robert-maillart/

Robert Maillart (1872–1940) Structural Engineer and entrepreneur. ETH Zurich ETH-Bibliothek. https://library.ethz.ch/en/locations-and-media/platforms/short-portraits/ robert-maillart-1872-1940.html

Robert Maillart and Structural Reinforced Concrete. http://scihi.org/robert-maillart/

Fivet, C. and Zastavni, D. (2012). Robert Maillart's key methods from the Salginatobel Bridge design process (1928). Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures 53(171):39-47.

Structures & Technologies LAB: Robert Maillart. https://uclouvain.be/fr/instituts-recherche/lab/struct-a

Robert Maillart: Betonvirtuose. https://vdf.ch/robert-maillart-betonvirtuose.html

Robert Maillart Lagerhaus der Magazzini Generali 1924–1925. https://www.atlasofplaces.com/architecture/lagerhaus-der-magazzini-generali/

Robert Maillart. https://structurae.net/en/persons/robert-maillart

Concrete: The building material of the 20th Century. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/culture/concrete--the-building-material-of-the-20th-century/47310640